As central bankers around the world continue to lament the lack of helpful fiscal policy and discuss the limitations of monetary policy after years of ultra-accommodative policy, we discuss what we see as a few of the potential risks to the outlook should the United States economy stumble or risk-sentiment takes a downturn.

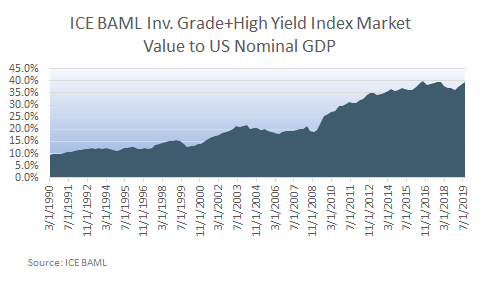

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has now lowered the Fed Funds target rate 3 times during 2H19, but we are concerned about the further utility of extremely low rates. Despite the fact that these rate decreases have led to easier financial conditions, both in the United States and globally, the most recent commentary from the FOMC itself suggests a pause in rate cuts is now the base case. Moreover, much of the firepower of the extended period of zero and low interest rates has flowed to corporations rather than the consumer. This has resulted in significantly higher debt levels among companies (particularly in the US but also globally), as evidenced by the fact that the triple-B tier of the corporate debt market now makes up over 50% of the ICE BAML Investment Grade Corporate index, marking the first time more than half of the index is at the lowest investment grade tier. And, while Federal Reserve data about nonfinancial debt as a percentage of GDP points to a cyclical high of around 46% (this statistic tends to fluctuate between 35 and 45 percent), index-eligible debt as a percentage of GDP has made new highs for most of the period since 1990. This is extremely important because this debt, unlike bank loans or private securities, is held by institutional investors, mutual funds, and ETFs. That debt is traded regularly and furthermore it would likely cause significant pain during a market sell-off. The financial ratings criteria for a triple-B (lowest investment grade tier) versus double-B (this highest speculative grade tier) have deteriorated significantly during the expansion, potentially leading to a large increase in downgrade activity to below investment grade.

As with consumers prior to the financial crisis, corporations are in a weak position to withstand a downturn in revenue relative to debt burdens. Further, we believe the environment of very low or even negative interest rates by many central banks, including the Federal Reserve, has forced the misallocation of capital into esoteric corners of fixed income markets. That assertion conveys a finding the International Monetary Fund has made in its most recent Global Financial Stability Report. More specifically, money is flowing to potentially less creditworthy entities, and in some new and novel ways that have not been tested during a period of slowing economic activity. Credit has been allocated to enterprises against a backdrop of unrealistic financial performance assumptions and with significantly fewer creditor protections. In some cases, this credit has either been packaged into securities and sold to yield-hungry investors as new types of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) or sold as a new asset class (the rise in “private credit”).

Further analysis supports our contention that the imbalances that have been created by the extended era of easy money since the end of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) has potentially significant consequences for what occurs during the next downturn from both a financial health and market performance perspective. We are somewhat more concerned, however, about the transmission mechanism from Federal Reserve policy to the United States consumer who is currently the growth engine for the entire US domestic economy, and with it the world. Credit card rates, for example, are currently just under 17% on average, which is virtually the highest on record in Federal Reserve data going back to 1993. Similarly, if we look at the average financing rate for new automobiles, the level currently stands at 6.7%, up from 4.5-5% for much of the economic recovery and roughly the same level reached during the GFC.

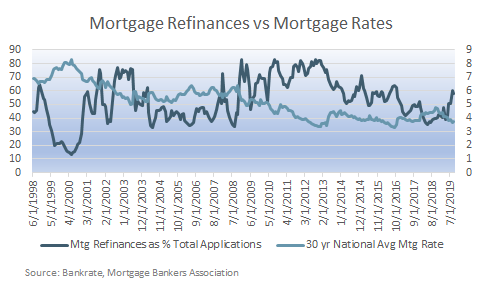

While mortgage rates have benefitted more from the move downward in US treasury rates, one could argue that much of the refinancing activity has already occurred, given the extended period of very low rates. Also, a large majority of Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp (Freddie Mac), and Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) mortgage origination now occurs in the non-bank space, which relies on short-term borrowing as opposed to a combination of deposits and other funding that could potentially be curtailed in a downturn (again, disrupting the monetary policy transmission mechanism). These entities currently originate about 70% of Fannie and Freddie mortgages and nearly 90% for Ginnie, according to a recent presentation to the Financial Stability Oversight Committee prepared by the Fed, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (as reported by Bloomberg).

For those readers that would like to further explore these topics, we encourage a perusal of the aforementioned International Monetary Fund Global Financial Stability Report, which explores many of these topics in depth, and also provides an array of interesting charts (link below). For those interested in reading about the non-bank mortgage origination story, that link is included as well.