“You have to remember one thing about the will of the people: it wasn’t so long ago that we were swept away by the Macarena.” – Jon Stewart

Having troughed in May, high frequency economic data snapped back sharply in June, albeit not to pre-virus levels. One such indicator – the Global purchasing managers’ index (PMI) markedly improved in June from 42.4 to 47.8; but remains in contractionary territory (Chart 1). June sentiment data were buoyed by gradual reopening in Asia, Europe and in the United States, as well unprecedented government support which blunted the economic fallout from the widespread lockdowns to slow the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. China’s PMI improvement was particularly encouraging both because China was the epicenter of the pandemic and because of the strong relationship between Chinese reflation and global growth.

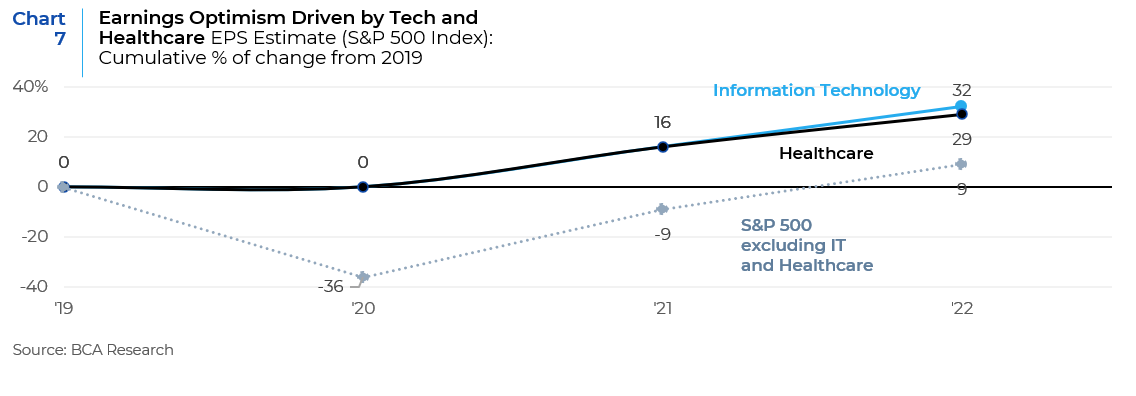

After benefiting from a snap-back from their respective lows, the path back to pre-COVID-19 levels will be a fitful and 2 to 3 year policy-driven slog. Positive high frequency data such as retail sales and even PMI will not resuscitate profits immediately, and need to be contextualized through the inconvenient truth of reciprocal math (i.e., a 50% snap back preceded by a 50% decline means that we are still 25% below the starting point). Accordingly, global earnings estimates (outside of the Info Tech and Healthcare sectors) also still fairly downbeat, suggesting that despite encouraging recent data, analysts are still expecting more of a U-shaped recovery. Moreover, global trade has yet to meaningfully revive, new export orders are still contracting after almost two years of contraction – and employment is still well below pre-COVID-19 levels. Therefore, governments will have to continue to prop up aggregate demand through income substitution measures in order to soak up surplus labor.

Risk asset prices will consequently trade nervously from here on in and the risks discussed in the balance of this paper could easily catalyze a 5% to 10% correction. However, we believe that these near-term risks will provide a buying opportunity. The U.S. dollar’s slide (about which we wrote extensively early this year), coupled with a material pick-up in Chinese spending on construction and infrastructure will favor non-U.S. assets in general and EM and commodity investments in particular. Although the greenback typically benefits from heightened economic and geopolitical uncertainty, the pandemic has exacerbated already structurally bearish dynamics for the U.S. dollar. Specifically, surging dollar supply due to the Fed’s monetization of U.S. public and some private debt as well as soaring twin deficits (i.e., the combination of the fiscal and current account deficits) are highly dollar negative. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, the twin deficit was estimated to rise to 7.5% of GDP by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Now the U.S. fiscal deficit alone will be approximately 11% of nominal GDP for 2020, if not higher. Moreover, stimulus in China will be a key transmission mechanism to boost global growth. The National Peoples Congress has fully abandoned its post 2015 deleveraging objective and announced a goal of creating 9 million new jobs by boosting credit and fiscal spending, particularly through the construction and infrastructure sectors that the government can most directly impact. These import thirsty sectors would be expected to boost commodity prices, as well as the industrial metals and machinery sectors.

Given the size of the global output gap (estimated at $9 trillion by the IMF), global bond yields will rise modestly over the next few years, but could be at risk longer term (3 to 5 years) when the inflationary impact of diminished supply chains, anti-globalization, a reduced support ratio (i.e. the ratio of retirees to work force participants) and monetary accommodation come home to roost. In the interim, in addition to EM debt, fixed income investors should continue to overweight sectors being back-stopped by the Fed (i.e., high quality agency, asset backed investment grade corporates) and thus shielding investors for incurring economic risk. The risk of another downturn challenging the default adjusted rates for issues below the BB level is significant, without equivalent central bank support.

Market Recap

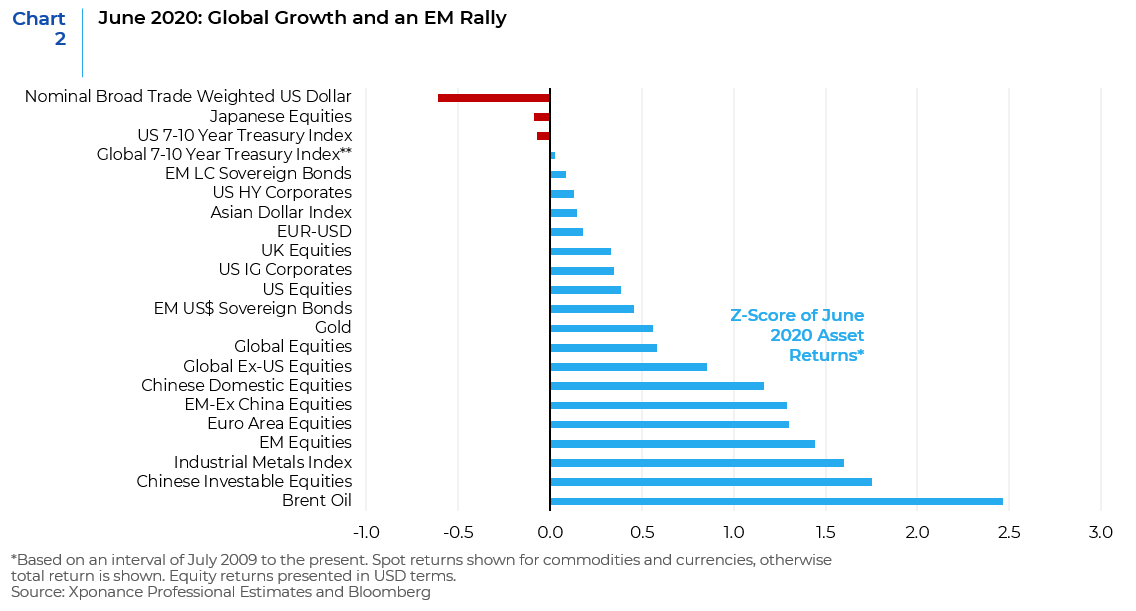

During the month of June, cyclical assets, such as Brent crude oil, industrial metals, and emerging market equities performed the best and safety assets, such as the US dollar and treasuries performed the worst (Chart 2). In China, the epicenter of the pandemic, the market received confirmation that economic reopening will lead to a revival in business and consumer activity. Meanwhile, government authorities dispelled doubts about policy support via a surge in private credit (total social financing). Consequently, Chinese investable equities performed second best in June, whereas they were third worst in May.

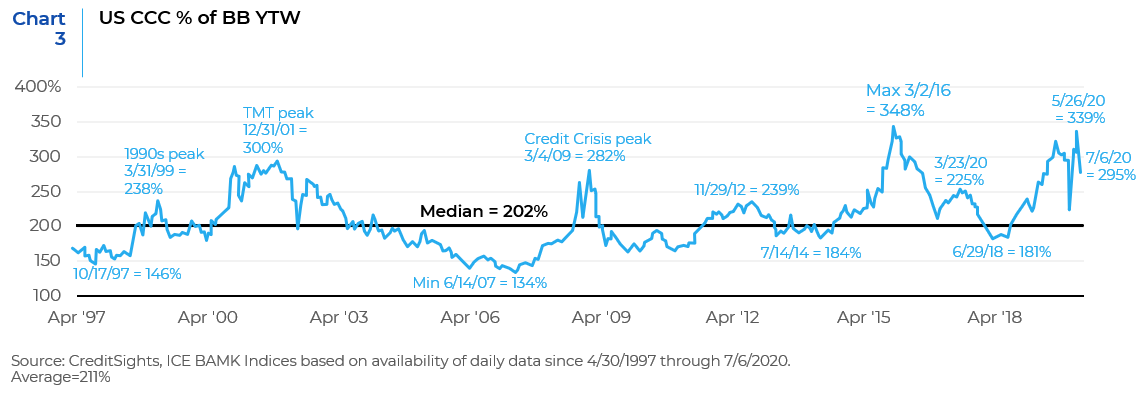

Over the full year to date period, U.S. treasury bonds have outperformed credit issues. In the month of June, U.S. dollar-denominated EM sovereign debt and BBB issues performed at the top of the heap. Throughout the year spread volatility drove performance and the lack thereof for credit sectors. For example, high yield spreads widened to the third highest level since the late 1990s, (the first two being the second half of 2008 and the first half of 2009). The Fed’s massive response, along with the $510 billion PPP program has thus far averted concerns over solvency and the dramatic fall in rates sparked a credit issuance wave not seen in years. However, default assumptions tend to be a lagging indicator, so it remains to be seen how high yield and particularly, CCC paper responds to the invariable air pockets discussed below. For example, on a yield to worst basis, CCCs are currently 295% of that of BB credits, vs. a median ratio of 202% since 1997 (Chart 3). While this ratio is below the March high of 348%, one wonders whether CCC paper is pricing for unforeseen doom (default) or have BB gotten ahead of themselves?

Ultimately, the global recovery will be fitful and shaped by government policy responses. For example, China’s pandemic-related fiscal measures buoyed industrial production and eased credit availability; whereas U.S. fiscal support has been more focused on stop-gapping consumer income and alleviating insolvency risks. However, as anyone who has watched a horror movie knows, the scariest part of the film is the one before the monster is revealed. No matter how good the makeup or set design, our imaginations can always fathom something much more frightening than Hollywood can create. COVID-19 is a deadly disease, but at this point, it is a “known known.” The next few months will bring news reports of overflowing emergency rooms in some U.S. states, delayed reopening, and talk of renewed lockdowns. The knee-jerk reaction among investors will be to sell stocks. As was the case during the first wave, the latest outbreak will likely be brought under control through a combination of increased voluntary social distancing and the cessation of activities that are known to significantly contribute to the spread of the disease, such as bars and nightclubs. Similarly, while the political machinations over the late July fiscal cliff are likely to spur market volatility, there is no discernible political support for returning to fiscal austerity despite the material rise in debt to GDP ratios here in the U.S. or globally. Another bogeyman, the potential of a democratic party sweep of all three branches of government in November; is for the most part, already being priced into markets. While most of these risks discussed below are known and therefore priced into asset prices, we note two risk possibilities that could exceed expectations. The first is a more virulent and deadly mutation of the coronavirus or even more ineptitude in public health responses. The second could arise from even greater geopolitical bellicosity from the Trump administration, if President Trump’s re-election chances continue to wane.

1. Policy Fatigue and Fiscal Cliff

On the policy front, fiscal stimulus continues to be rolled out at unprecedented levels in the U.S., EU, China, and elsewhere. In the U.S., the so-called fiscal cliff (i.e., the expiration of direct payments to U.S. households and additional unemployment insurance stipends) at the end of July remains a source of uncertainty. Since these measures in combination with the PPP amount to around 5% of U.S. GDP, should this risk be realized, it would be material. Fortunately, it is in neither political party’s interest to see this happen. Therefore, we expect the U.S. to implement another round of fiscal stimulus measures ranging from $2 to $3 trillion before mid- August. As with the political show down over expanding the U.S. debt limit in 2011, negative market reaction to the equally likely political drama preceding an agreement will provide a buying opportunity. This is especially the case because there is a great deal of certainty around monetary policy accommodation; with the Fed forecasting that it will keep rates at zero through 2022.

2. The Reaccelerating Spread of COVID-19

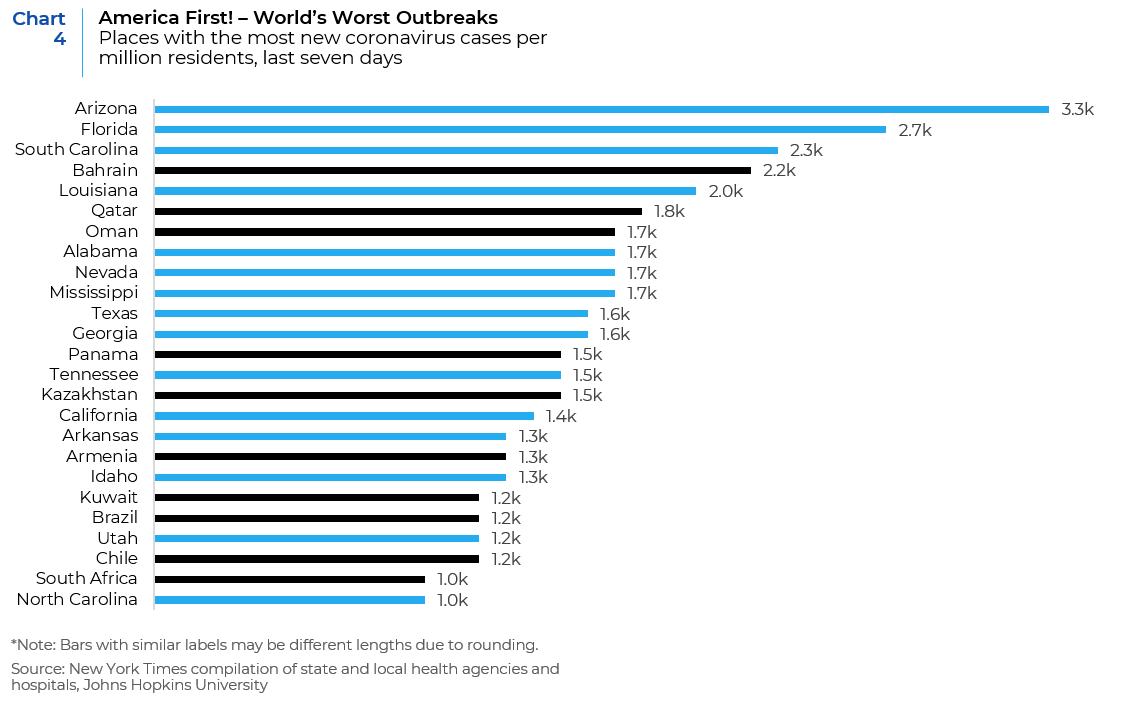

At the global level, the number of new infections has continued to accelerate. This past month, new cases reached around 200,000 per day, with the U.S. being by far the largest contributor at 50,000 per day (Chart 4). Among emerging economies, case numbers have continued to rise, even while lockdown measures are being eased. As with developed countries, the results vary with countries in north Asia (Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore) as well as parts of Emerging Europe, appearing to have brought the virus under control. But Brazil has failed to control the virus, even while lockdown measures have eased anyway. In India, cases remain on a sharp upward trajectory and limited testing means that the situation is almost certainly worse.

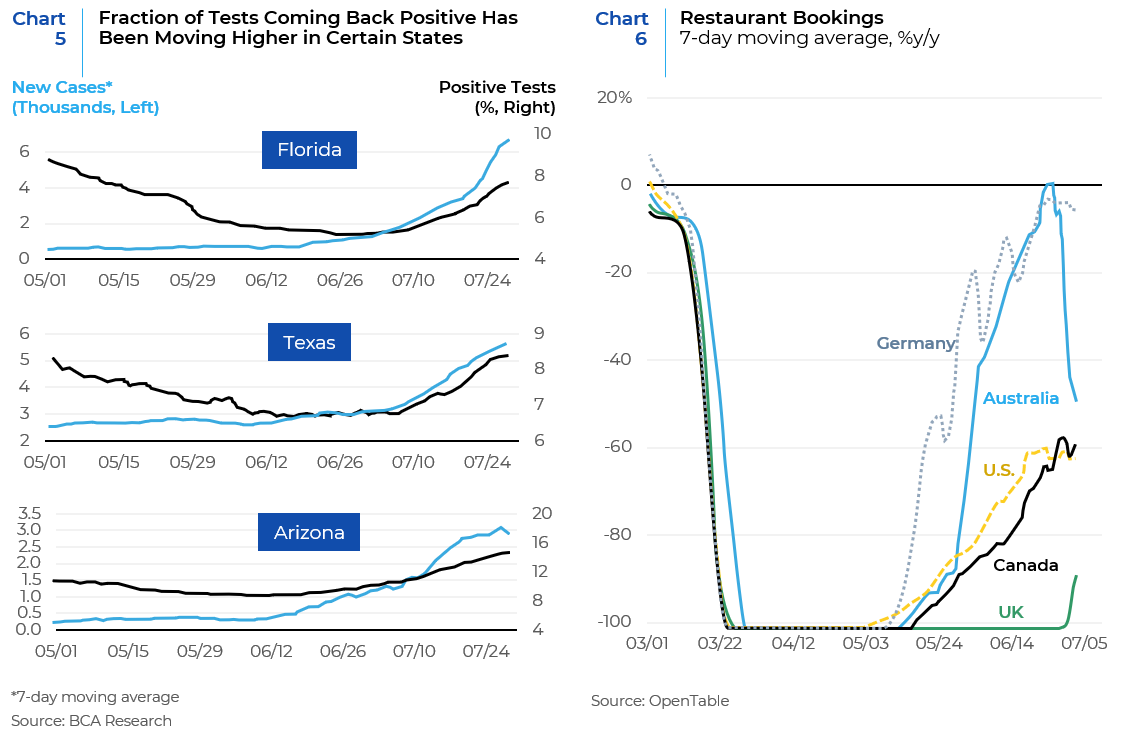

In the U.S., the public health response has been inconsistent and disappointing and reaccelerating cases have caused some states to dial back the pace of reopening the economy. While testing has increased, the material jump in positive results as a percent of tests performed as well as hospitalizations suggest that we are either reaccelerating the first wave or at the beginning of a second wave (Chart 5). Putting aside the serious and material health considerations, what matters for investors is the economic consequences of the public health response. Without a proportionate spike in death rates (which are slowing relative to the initial outbreak due to improved public health measures such as isolating the most vulnerable, improving reaction times and better therapeutic measures), we believe that another global lockdown is unlikely; as both governments and consumers lack the will to impose another long-lasting, draconian shutdown. Thus it is unlikely that the virus’ resurgence will torpedo the global economy; but it will challenge assumptions around a V shaped recovery. Indeed, timely indicators such as restaurant reservations suggest that increased consumer caution is already taking a toll. The previous upward trend in the U.S. seems to have stalled, due partly to developments in the affected southern and western states. Meanwhile, even the relatively small and localized outbreak in Australia has caused bookings to nose-dive (Chart 6).

3. Labor Market Dislocation

Another risk is labor markets healing more slowly than anticipated. Loosening containment measures have allowed some people to return to work, but incomes are still depressed, with further layoffs to come. While job retention schemes have been effective at limiting the rise in unemployment in non-U.S. Advanced Economies (in Japan, the unemployment rate was just 2.9% and in the euro-zone, the unemployment rate edged up from 7.3% to 7.4% in May), they won’t protect workers indefinitely. In the U.S., the 4.8 million increase in non-farm payrolls in June offered further confirmation that the initial economic rebound has been far faster than anticipated; but employment remains 14.7 million below its February level and high-frequency data suggest that activity is stalling. On the back of this, the pace of job gains will be much weaker over the coming months, with the recovery likely to be bumpy.

4. Earnings Risk

Bottom-up S&P 500 earnings estimates for the next year are optimistic and are little more than extrapolations. But it is important to note that these estimates are entirely being driven by the Info tech and Health Care sectors. Outside of these two sectors, earnings per share (EPS) is still expected to be down 9% next year relative to 2019 (Chart 7). Moreover, the EPS of cyclical stocks (industrials, energy, financials, consumer discretionary), the first two of which would be expected to benefit from Chinese reflation and a weaker dollar, are discounting a 50% decline in earnings for this year and 19% decline next year vs 2019. Globally, earnings estimates are also still fairly downbeat. This suggests that analysts are expecting more of a U-shaped recovery.

5. Political Uncertainty and Geopolitical Risk

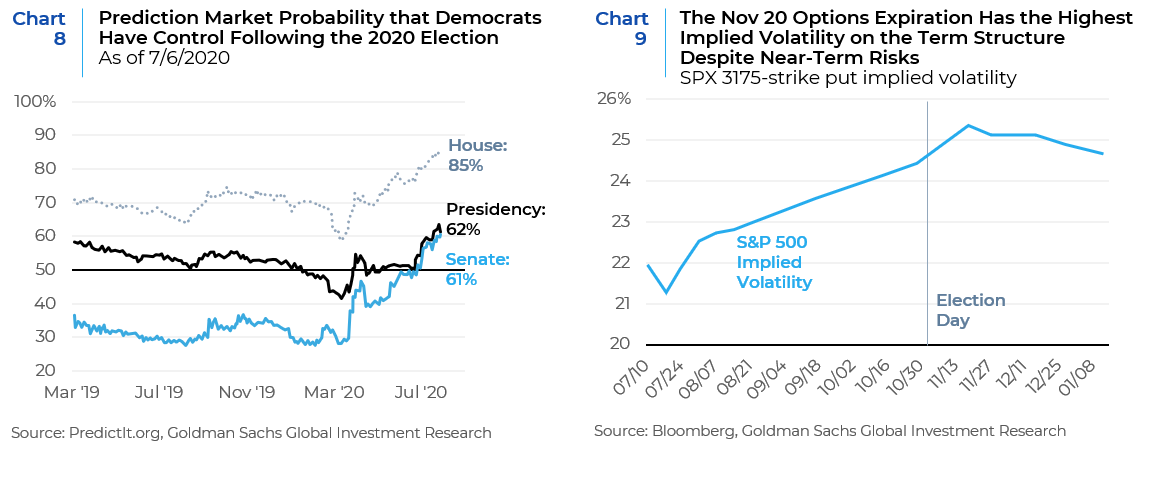

The U.S. election dynamic has shifted heavily against President Trump due to the administration’s uninspiring and inconsistent responses to both the COVID-19 outbreak as well as the social unrest catalyzed by the killing of George Floyd. Accordingly, the Real Clear Politics poll average shows presumptive Democratic party nominee Joe Biden with an 8.8 point spread over the incumbent Republican Donald Trump (49.3% vs.40.5%). FiveThirtyEight shows Biden ahead in a head-to-head election by 9.6 points (51.1% vs. 41.5%). Commentators are concerned that Democratic control of the White House, Senate, and House of Representatives is market relevant and not being fully appreciated by investors. But betting markets clearly predict a Democratic Party sweep (Chart 8).

Moreover, investors appear to be predicting a contentious election. Despite heightened near-term risks, including the COVID-19 resurgence and the upcoming expiration of fiscal measures, option markets are pricing larger election risk than in prior cycles through a bump in the VIX futures curve around the November election (Chart 9). One reason for the increased election uncertainty is that health concerns and social distancing protocols suggest that more voters will decide to vote by mail instead of casting ballots at traditional polling stations on Election Day. This would delay the tabulation of the winner and if the 2000 election is any guide – invariably requiring a re-count of all the absentee and mail-in ballots if the election is close.

Equity investors have correctly focused on tax policy in evaluating the risks of a Democratic sweep. According to the Tax Foundation, the former Vice President’s plan would raise the statutory federal tax rate on domestic income from 21% to 28%, and reverse half of the cut from 35% to 21% instituted by the 2017 TCJA. In addition, the plan would double the GILTI tax rate on certain foreign income, impose a minimum tax rate of 15%, and add an additional payroll tax on high earners. Goldman Sachs estimates that the Biden tax plan would reduce S&P 500 earnings estimate for 2021 by roughly $20 per share, from $170 to $150. Combined with a drag on U.S. GDP, they estimate a total drag on 2021 EPS estimates by roughly 12%.

Additionally, Health Care stocks and potentially, social media stocks may also face considerable regulatory risk. The Health Care sector has outperformed this year due to its earnings resilience during the pandemic. It is also one of the sectors that is expected to structurally benefit from an aging population. Bottom-up consensus forecasts currently show Health Care EPS growing at a 6% CAGR between 2019-2021, second only to the 7% estimate for the Info Tech sector. While earnings strength has supported the performance of Health Care stocks so far this year, the sector trades at nearly its lowest relative valuation multiples on record with valuations that have correlated in recent months with the rise in Democratic election odds. The Info Tech sector could also face heightened regulatory risks. Potential risks to this sector could manifest in the form of more forceful anti-trust measures and/or regulations attaching a dollar amount that users will have to be paid to surrender their data. These measures are already gathering steam in Europe and California and are not priced into this sector’s 30% profit margins.

Geopolitical Risks

As has been observed elsewhere, nationalism is on the rise globally. In keeping with its increasingly aggressive assertion of regional hegemony, China imposed a controversial national security law onto Hong Kong, inviting sanctions from the United States. Meanwhile, Russians voted to enable President Vladimir Putin to remain in power until 2036. U.S.-China talks are keeping a lid on tensions and preserved the Phase One trade deal for the time being. But these geopolitical trends portend more struggle between the great powers even as global trade continues to shrink. If President Trump’s re-election chances continue to decline, a clear and unpriced market risk could arise from increased geopolitical bellicosity in order to rally voters around a foreign enemy; most likely China but possibly Europe. This is an unpriced risk.

A Biden win would not necessarily abate anti-China sentiment, but it would abate the current administration’s seeming hostility towards multinational alliances. To the extent that a Biden administration results in less bellicose stoking of geopolitical tensions, risk premia should contract and thus be market positive.

In conclusion, now that the policy fueled bounce-back from depressed pandemic-levels has occurred, the recovery in both the real and financial economy will be a bumpier slog; with multiple speedbumps along the way. In addition to the other risks discussed herein (fiscal cliff, slower reparation of the labor market, political/geopolitical and earnings surprises), the rapid re-acceleration and increased positivity rate of COVID-19 cases in U.S. sunbelt states promise even greater volatility; with a 5% to 10% correction likely. However, we see any such pullback as a buying opportunity, or minimally, one in which institutional investors should maintain or increase their allocation to risk assets. Re-accelerating COVID-19 cases will certainly weigh on global growth over the coming months, but there is limited political appetite for the broad-based economic dislocations experienced in March. While we recognize that the long-term impact of unabated fiscal profligacy and debt to GDP ratios will be material; this year there is little political appetite to pull back on the extraordinary policy stimulus that has buoyed financial markets, stop-gapped income levels and allayed solvency risks. Moreover, institutional investors’ skepticism about the post-March rally (with U.S. cash holdings up almost 12% from the start of the year), provide substantial dry powder to power its next leg. This time around, we would recommend a greater focus on cyclical sectors, non-U.S. and particularly Emerging Markets assets that are most leveraged to a softening greenback as well as China’s ramped up infrastructure and construction spending.

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospects for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct, but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.