2023 portends no less turbulence. The world grapples with a series of large magnitude macro-economic and geopolitical uncertainties. Chief among these are:

- How much and how fast will rates rise?

- Will inflation mean revert or will more demand destruction be needed first?

- How much will GDP and earnings fall relative to expectations?

- Will Chinese stimulus drive global growth at it did in 2009 and 2016?

- Will Putin expand his war beyond Ukraine?

For each such large magnitude question, there are hundreds of answers from economists, strategists, and pundits, some of which are sure to be right. For those interested, the Financial Times has prepared a convenient compendium of many such global outlooks. We are also concerned with these questions. But they are ultimately all questions without answers today. The equivalent of ship captains guessing on what exotic and exciting shores might lie over the horizon. Instead of adding more ink to extol on uncertainties, however, we want to focus here on a more familiar, but thus less colorful destination for our metaphorical mariners, that we do not see getting the coverage it deserves. Namely, that structurally higher inflation and interest rates will very likely create an historical step change in asset allocation among the preponderance of U.S. pension funds, and possibly most U.S. investors. What is driving this resetting of rates is a structural change in inflation dynamics, driven by an historic supply shortage of workers in the U.S., as well as other structural changes that were discussed in prior research notes. Moreover, the Fed’s quantitative tightening program to shrink its massive post-pandemic $8.5 trillion bond portfolio will continue to drain liquidity from the bond market, putting further pressure on both rates and volatility. These factors we believe will likely to persist for years regardless of many of the geopolitical and global economic uncertainties that are occupying so much airtime today.

The net effect on the fundamental jobs of our clients (asset allocation and manager selection) will be to push traditional fixed income back to the forefront of investment decisions for the foreseeable future. Whilst in the short-term, bond prices don’t typically thrive during periods of high inflation volatility, once inflation has stabilized, even at a higher structural level, higher nominal rates will provide a terrific entry point and total return opportunity which has not been in place for over a decade. U.S. pension funds’ fixed income allocation are well below historical levels, as they have been primary funders of burgeoning alternative portfolios. We see this past year’s market upheaval as leading to an historic great rebalancing back to traditional fixed income.

Structural Inflation & Quantitative Tightening Will Create a New Lower Bound for U.S. Rates

As we wrote extensively last quarter, we believe that we are emerging from a period of aberrantly low structural inflation globally. The ending of these global disinflationary forces will be further compounded by a marked uptick in inflationary forces that are uniquely strong in the U.S. Wages have been on the rise in the U.S. since the GFC and were already hitting the Fed’s threshold of 2% in 2019, before the pandemic (Chart 1).

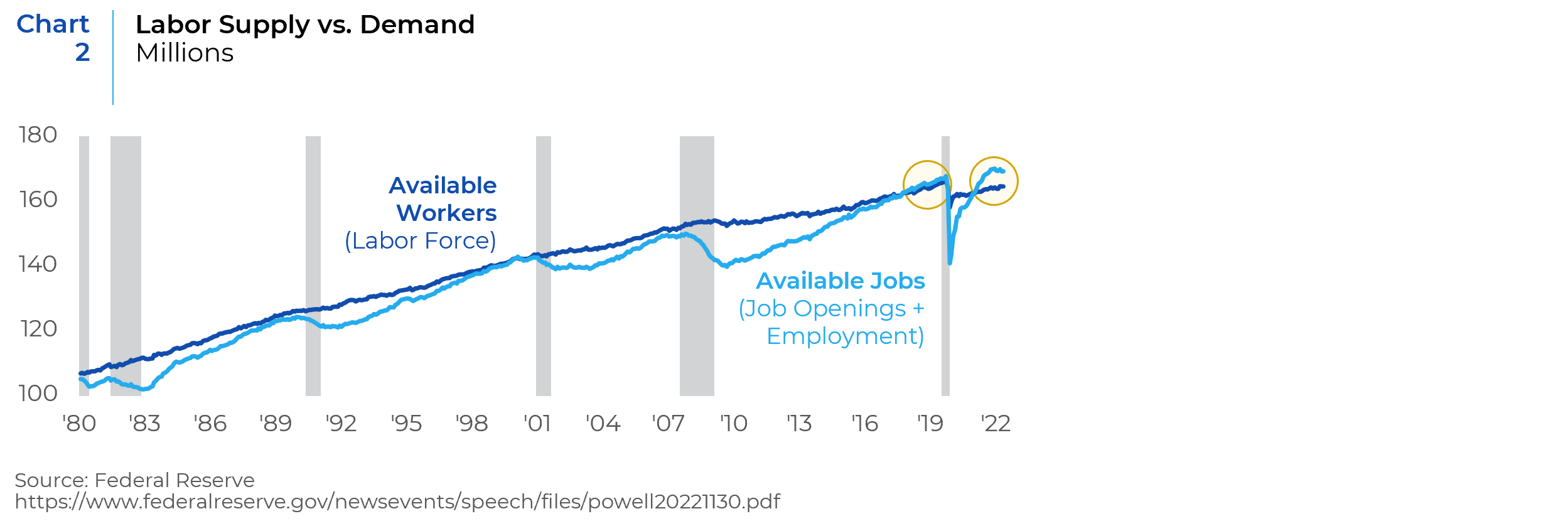

Rising wage pressures have emanated from a confluence of U.S.-specific supply-side factors that are independent from more market-based demand-driven pressures. The uneven demographic distribution of Baby Boomers vs the Gen Z cohort, restrictive immigration policies, and changes in worker preferences were among the drivers in this slow, but steady uptick in wage pressures from 2010-2020. These supply side effects had already created the largest labor supply gap in the U.S. economy since the late 1960s, even before the pandemic. (Chart 2). The pandemic and the massive fiscal transfers that were designed to ameliorate its economic devastation further exacerbated these trends and exploded the supply gap of labor to where it is today.

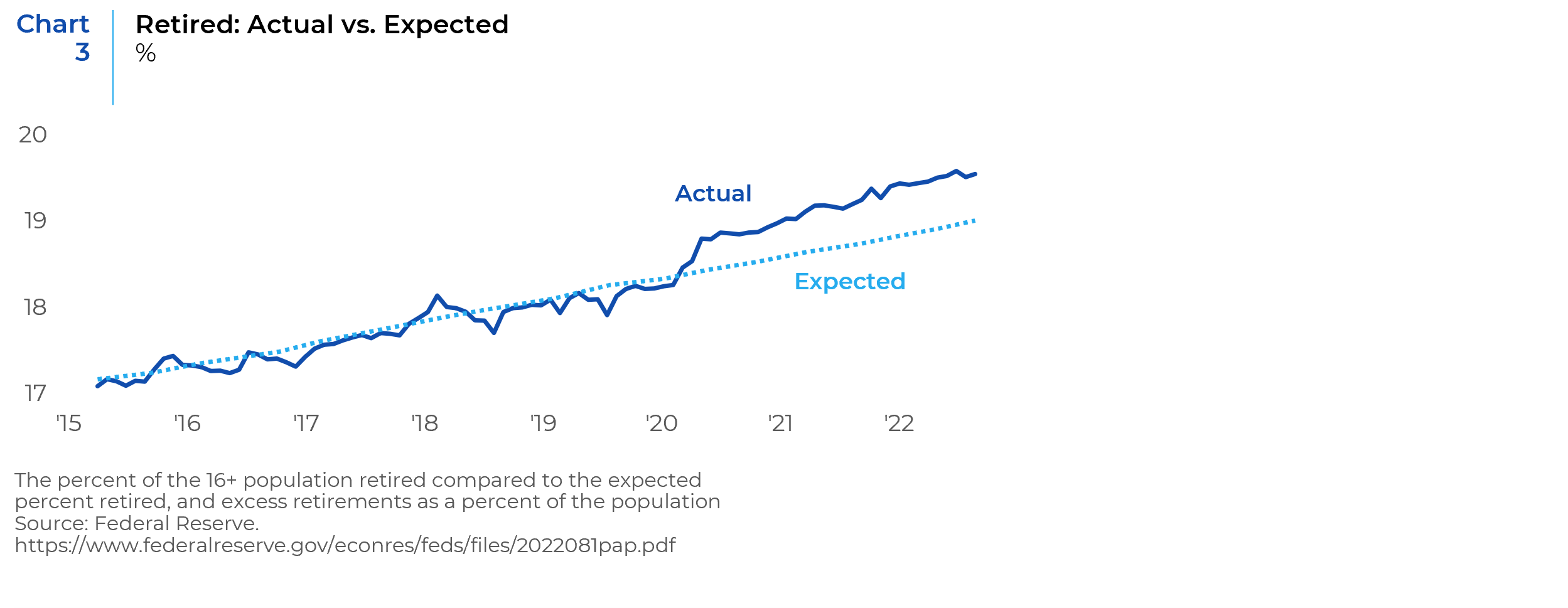

Recent research by Fed economists further breaks down the causes of the post-pandemic labor supply gap. Of the estimated 3.5 million worker supply shortage, the largest contributor, or about 2 million people, is excess retirements since the pandemic began (Chart 3).

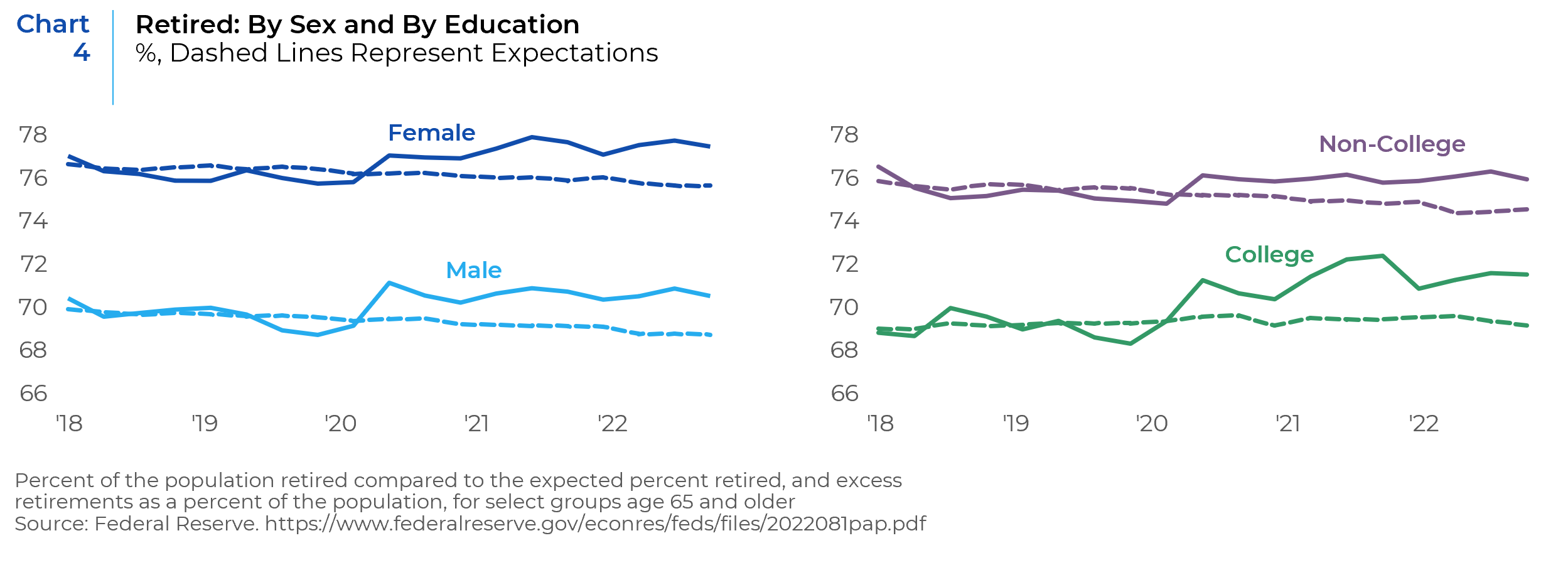

Moreover, these excess retirements have come equally across genders and among those with or without college degrees, indicating remarkable persistence in the trend (Chart 4).

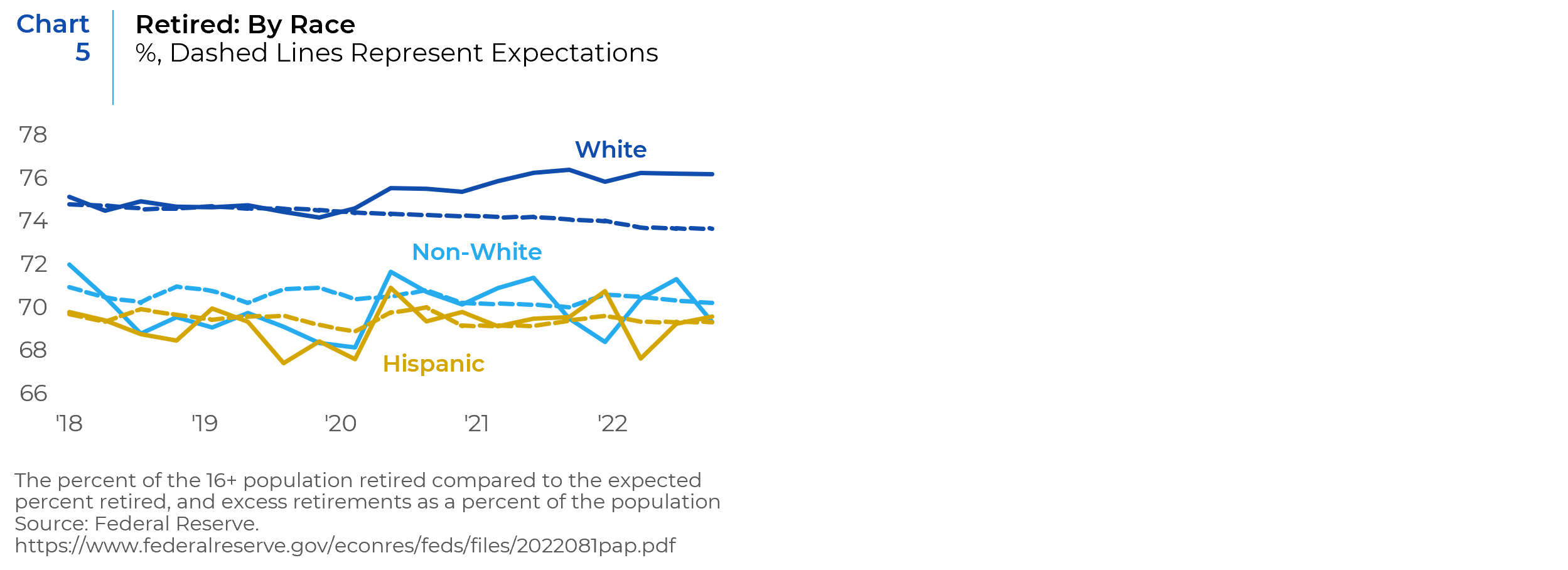

Interestingly, the Fed study found that these excess retirements occurred almost exclusively among white, non-Hispanic workers (Chart 5). The Fed researchers’ espoused theory on this is that this “group had higher pre-pandemic wealth holdings and hence a larger financial cushion, …to support greater early retirements.”1 For Xponance and our clients, this reminds us of the importance of our own work as a small part of the larger struggle to redress our nation’s race-based economic inequalities.

For the Federal Reserve, and for those worried about further rises in interest rates, of most imminent concern is that the pace of these retirements has not abated, let alone reversed course. As Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell said in his November 30, 2022 speech at the Brookings Institute, “older workers are still retiring at higher rates, and retirees do not appear to be returning to the labor force in sufficient numbers to meaningfully reduce the total number of excess retirees.”2 Indeed the Fed’s labor study noted that “the stock of excess retirements is currently so large that it would take a substantial and sustained increase in unretirements or decrease in retirements to fully normalize the retirement share over three years.”3 In other words, the Fed doesn’t expect these excess early retirements, and their concomitant impact on labor supply, to abate anytime soon.

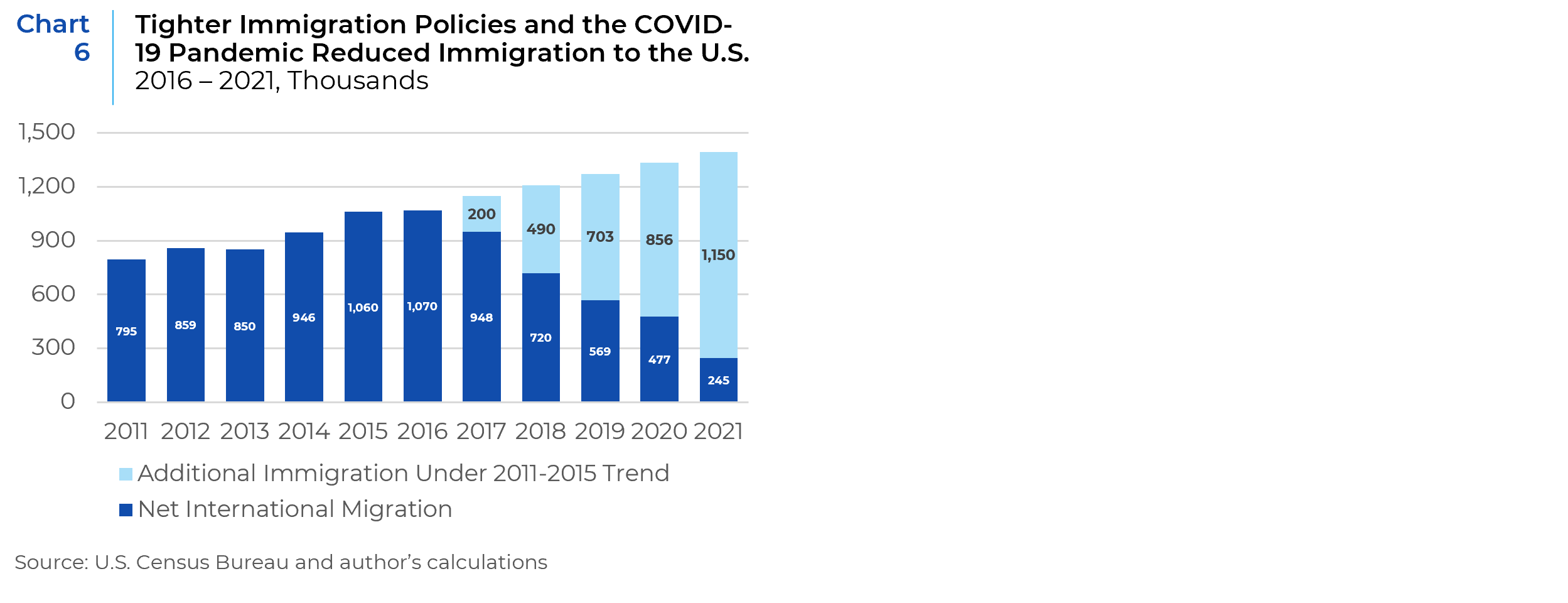

As was mentioned above, excess early retirements only account for about 60% of the current labor force shortfall. Another major contributor is a restrictive immigration policy, begun during the Trump Administration, but exacerbated by pandemic restrictions that the Biden Administration has continued (Chart 6).

Long-trending demographics are also at play. Absent a material change in immigration levels, the growth rate of the working age population is not expected to increase from its near-zero level until 2030.4 Finally, of the estimated 1 million American lives claimed by Covid-19, an estimated 400,000 of those were in the labor force.5

While supply shortages in labor portend an ongoing pressure on wages and thus inflation, the Federal Reserve is also expected to begin shrinking its $8.5 trillion balance sheet, of which the largest components are approximately $5 trillion in U.S. Treasuries and $2.6 trillion in residential mortgages. While the pace of this quantitative tightening remains highly uncertain, we consider the direction to be another “known known” for the next several years. This selling pressure, or even just the threat of it, will also help to keep interest rates higher for longer.

The Fed and the World React To Persistent U.S. Inflation

With a tighter for longer labor supply in the U.S., we believe that U.S. inflation will struggle to get below 3.5%-4% absent draconian rate hikes. We also believe that the Federal Reserve will not have the stomach to force economic and financial catastrophe to get back to its old target of 2% and will eventually settle into a higher inflation target of 3% to 4.5%. Indeed, the Federal Reserve already appears to be laying the groundwork for such an opening. In his November 30, 2022 speech at the Brookings Institute, Fed Chair Jay Powell plainly said that “Policies to support labor supply are not the domain of the Fed: Our tools work principally on demand.”6 It appears that the Fed is making a concerted effort to segment inflation emanating from supply-driven labor shortages as opposed to demand-driven forces. Such a distinction gives the Fed space to adjust their 2% target while still claiming to have done their job in quelling demand. However, we do not foresee the Fed walking rates back down from current levels, absent a return to 2% inflation (or a significant economic dislocation). Rather, we expect the Fed to use this supply vs demand distinction to justify a lack of further rate hikes despite not bringing inflation fully to heel.

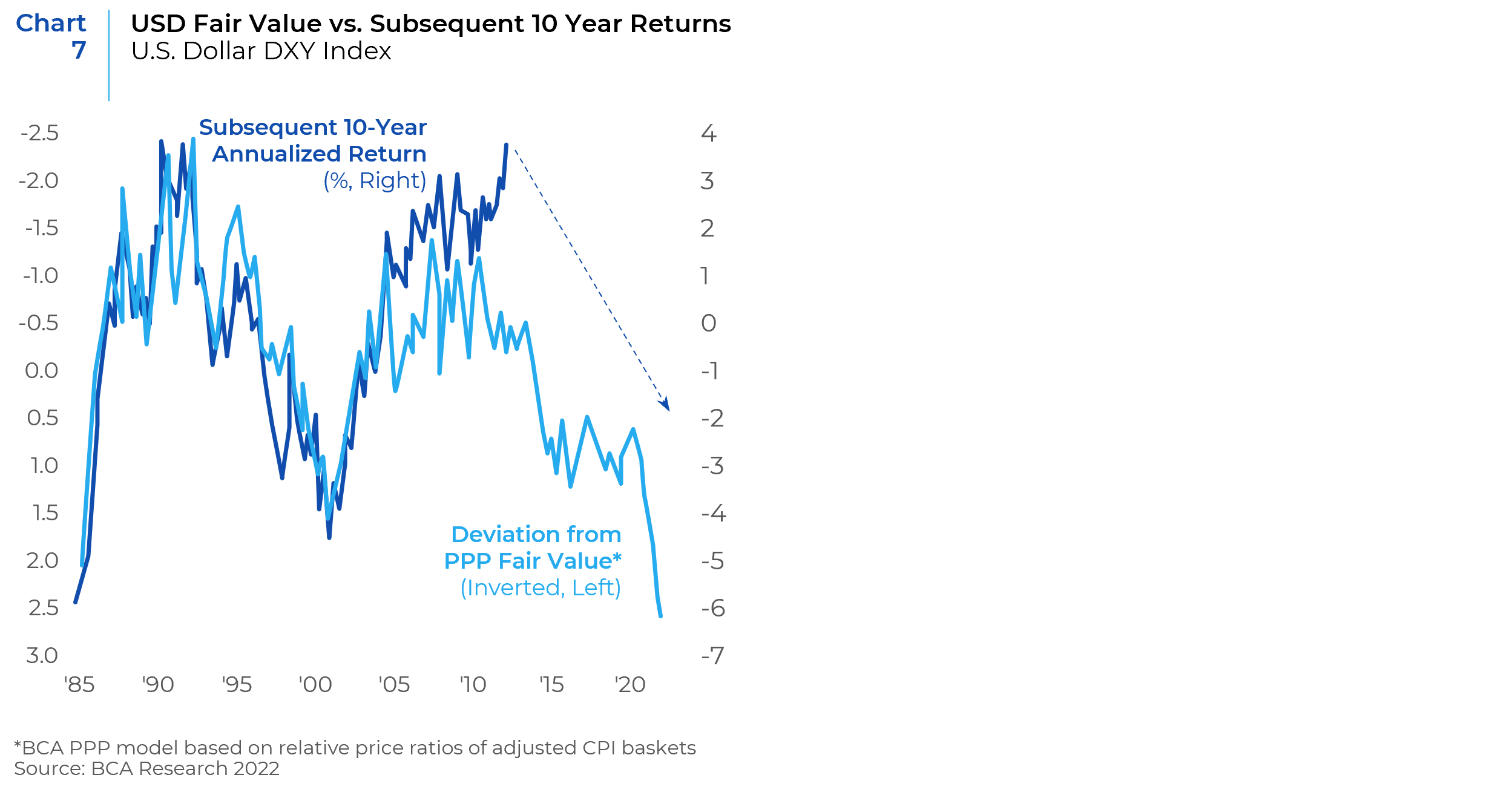

In a world of persistent 3-5% U.S. inflation, Fed rates seem most likely to stay anchored near a real rate of zero to slightly positive. Combined with any material unwinding of the Fed’s balance sheet, allocators should anticipate nominal corporate rates in the 5-7% range for the next several years. These levels become very attractive for USD investors, in particular pension funds, who will then need to take very little risk to achieve their return targets. But if this structural inflation persists in the U.S., while Europe and Japan in particular see their inflation abate (or in the case of Japan, fail to pickup materially), real rates in those economies could be higher than the U.S., despite lower nominal rates. A lower real rate of interest would be enough to drive foreign investors away from U.S. debt holdings, or at least make them non-buyers if not outright sellers. As foreign investors today make up 33% of the holders of U.S. public debt and 23% of U.S. corporate debt, this is also a factor that could put further upward pressure on U.S. bond yields.6 Additionally, the USD is already at very expensive levels according to most fair value metrics and the long-term outlook for the USD compared to its trading partners is decidedly bearish (Chart 7), further reducing the appetite for foreign holders of U.S. debt.

A Return to Boring

In this new world of persistently higher nominal U.S. rates, we think a great rebalancing is at hand. For most U.S. public pensions, the rebalancing will be to add significantly to their historically low fixed income allocations. It should follow that the 2 million new excess early retirees, as well as the rest of the baby boomer cohort, are likely to also add to their fixed income allocations at these rates. This is not at all to claim that this will be the best performing asset class of 2023 or even the next several years. Nor would we even attempt to argue that today is clearly the best entry point for investment grade corporates. But for pensions seeking to match their long-term liabilities and able to hold bonds to maturity (or at least ride out some potential near-term volatility), it is unambiguously true that corporate rates at 5.5%+ solve a lot of problems for CIOs.

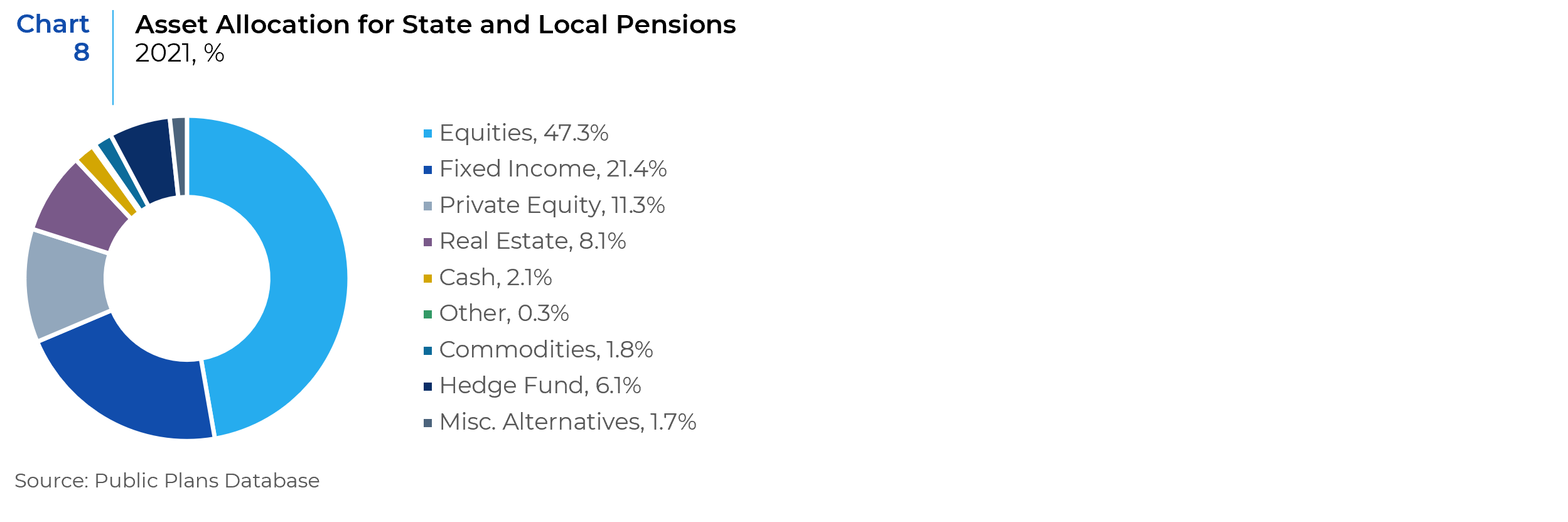

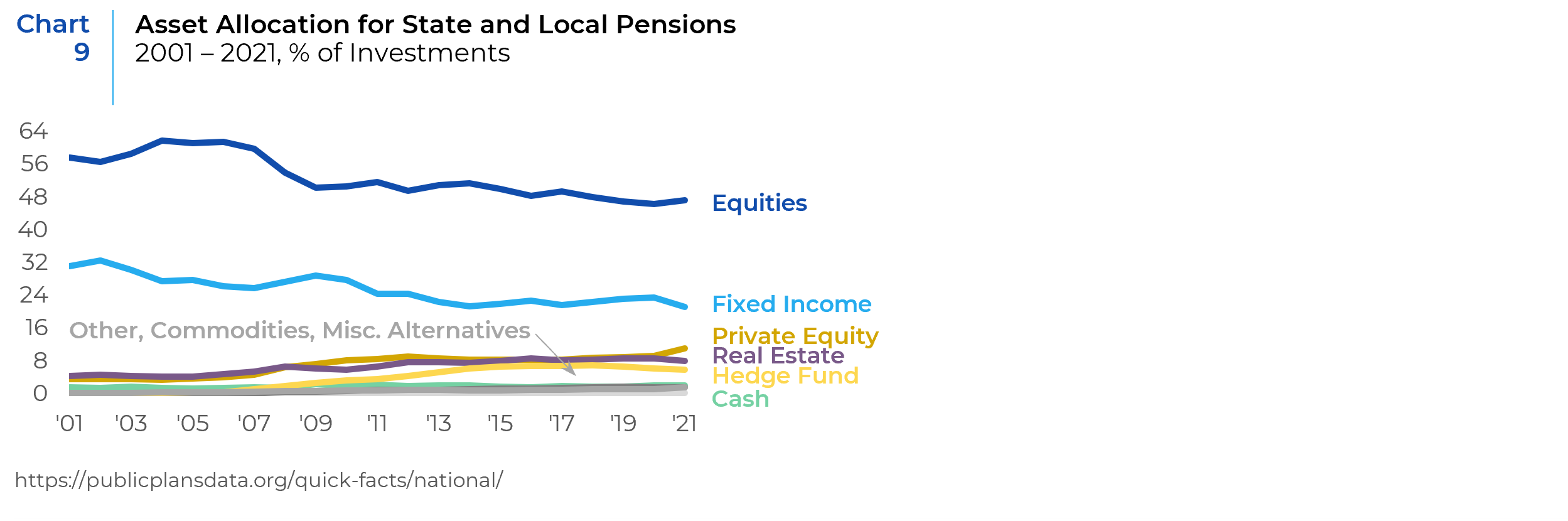

Rightly, U.S. public pensions shifted away from fixed income over the past 10 years and today they stand at the lowest share of public pension assets in U.S. history. Moreover, the U.S. stands out against its global peers in having a lower allocation to fixed income among all non-cash assets than all but three OECD countries.7 Pre-GFC, which also happens to be the last time U.S. corporate rates were at these levels, the average U.S. public pension allocation to fixed income was almost 40% higher than it is today (Charts 8 & 9). We believe it is reasonable to expect fixed income allocations to return to that level, or higher, during the course of this coming cycle.

Beyond liability matching, we believe a materially higher fixed income allocation solves other problems for the preponderance of DB and DC plans alike. All plan sponsors remain under pressure to cut overheads, either from internal staff expenses, external manager fees, or from operations. Relative to most other asset classes – but especially yield replacement strategies, such as market neutral hedge funds, private credit, or other alternatives which have absorbed fixed income’s space in plan sponsor portfolios over the past decade – larger allocations to traditional fixed income can cut costs in all three areas. Certainly the case to spend 2/20 to get a 7% yield from market neutral strategies feels substantially thinner in the present environment.

Water always takes the path of least resistance. The good news for investors is that today’s roiling ocean, while it may yet capsize some more boats along the way, a new channel is also being carved on the shores that can provide a wider berth of safe harbor for at least the next few years.

1 https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2022081pap.pdf

2 https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/powell20221130.pdf

3 https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2022081pap.pdf

4 https://www.conference-board.org/topics/labor-markets-charts/working-age-population-growth

5 https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/powell20221130.pdf

6 https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/20221209/z1.pdf

7 Australia, Lithuania, and Poland (where local pensions are not allowed to own government debt securities). https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/private-pensions/Pension-Markets-in-Focus-Preliminary-2021-Data-on-Pension-Funds.pdf

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.