This is the second of a three-part series on the two issues that led to 2024’s anti-incumbent party backlash. Part 1, The Precariat Are Still Mad – An Analysis of 2024’s Incumbent Party Shellacking, focused on the drivers behind spiking post-pandemic global inflation. This paper evaluates salient macroeconomic, demographic, and social factors that have or should inform immigration policy, as well as the policy solutions put forward by the incoming administration to address unauthorized workers in America. In Part III, we will evaluate the trade and other fiscal policy solutions that have been proposed, as well as their investment implications.

Key conclusions include:

- Two factors have historically driven unauthorized entry into the United States. The first is a response to the demand by the U.S. private sector for inexpensive labor. Over the roughly 100 years of U.S. immigration policy, expanding legal temporary worker permits for sectors where native U.S. workers are either unable or unwilling to meet this demand has been the most effective solution to the first factor. The second results from the historic refugee crisis taking place throughout the Western Hemisphere in response to significant political, environmental, and economic upheaval in countries such as Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti and Nicaragua. These people leave their homelands and families out of desperation, and not necessarily for economic opportunity. Solutions to this second “push” factor require a combination of greater resources to secure the U.S. border, requiring companies to better screen for immigration status, working with the source countries to reduce their level of privation, and with border countries to provide for a more orderly review of asylum applications, before entry into the United States.

- The ongoing policy failure to durably address the country’s broken immigration system partially reflects the United States’ nakedly transactional relationship with its immigrant labor. When jobs are plentiful, the country has urgently sought migrant labor, including undocumented workers, for jobs that native born workers scorn. When shrinking economic growth leads to fewer jobs for native born workers, those same migrant workers attract the ire of America’s job seekers and politicians. During such times, economic turmoil has led to scapegoating and populist foment. At peak moments of xenophobia, the U.S. has enacted mass deportations of its migrant population. These prior mass deportation efforts, described in the Insert on Page 2 (below), provide striking parallels to the current moment.

- As in the past, the current political rhetoric has been at variance with the reality of immigrants’ share of crimes committed in the United States and their substantial contribution to economic growth. Moreover, in a world in which populations are declining, America’s demographic exceptionalism is due to immigration.

- While mass deportations may satiate voter discontent, historically, they have not provided a durable solution. Moreover, another mass deportation of undocumented workers in the United States would increase inflation while lowering potential productivity and growth.

Insert – Prior Mass Deportation Efforts

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned “laborers” born in China from entering the United States, and China-born individuals already residing in the U.S. from obtaining citizenship or re-entering the country, was our first mass deportation effort. In 1880, the Chinese were the largest immigrant group in the American West. Their immigration was facilitated by the so called Six Companies,[1] which helped with legal processing, matching workers to employers, and organizing them into “gangs,” where one contractor, often a Chinese merchant, hired out a team of men. Since the gang provided their own housing, food and other services, Chinese workers were attractive to employers, who could deal with the contractor in English and did not need to provide amenities or support services for work that often took place in unpopulated areas. The most significant employment opportunity came from the Central Pacific Railroad who was competing with the Union Pacific Railroad (which was building the east-bound train line) to complete the transcontinental rail envisioned by the 1862 Pacific Railway Act under President Abraham Lincoln. The Act paid each rail company federal subsidies and land grants based on the miles of track they laid; thus, the race was on to complete as much track as possible. Between 1865 and 1869, the Central Pacific Railroad employed about 20,000 Chinese immigrants — as much as 90% of their workforce at the peak of construction. Though these workers would prove to be talented, brave, and productive, the railroad paid them less than their white counterparts, forced them to sleep in tents while white workers got to sleep in warmer box cars, and enlisted them to do the most dangerous jobs. The transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. It was a marvel of technological innovation, reducing the time it took to cross the United States from many months to a mere week, thereby uniting the nation.

But the speculation that followed completion of the railroad led investors to undertake massive amounts of debt and bid up the price of railroad bonds and real estate near train stops. Following the collapse of this speculative bubble, the financial crisis known as “The Panic of 1873” caused the unemployment rate to skyrocket to 14 percent. As the 1870’s “long depression” continued, Chinese workers became a target for mass deportation through the bi-partisan Exclusion Act. Its proponents argued that Chinese workers, who constituted 12% of the male working-age population and 21% of all immigrants in the western United States, reduced economic opportunities for white workers. However, a study by Nancy Qian, an economist at the Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management, concluded that the Chinese Exclusion Act led to negative economic effects for most non-Chinese workers and likely slowed the economic development of the western United States for many decades. Because the long distances and geographic dissimilarities between the West and the eastern parts of the U.S. made it difficult to fully replace the lost Chinese workers with others.

The second mass deportation of undocumented workers in the United States came in the 1950s under the Eisenhower administration. Estimates vary, but this program, derisively branded as “Operation Wetback,” swept up some 300,000 to 1.3 million Mexicans, many of whom had legally entered the country through joint immigration programs in the first half of the 20th century.

The parallels between Operation Wetback and the current moment are striking. Then as now, anti-immigrant rhetoric was pervasive, except that in the 1950s, it was trained primarily towards Mexicans. Mexican immigrants were portrayed as dirty, disease-bearing, crime-committing and irresponsible burdens on the country’s social welfare system. As with the Chinese, public discontent with illegal immigration exploded due to fears of job displacement after WW2, when jobs became more scarce. Accordingly, the American Federation of Labor’s Executive Council vigorously campaigned on the “wetback problem.”

Despite a widespread belief that Mexicans came to the United States to steal jobs from American workers, many had been invited to work in its fields through prior work permit programs. In 1942, for example, the U.S. Mexican Farm Labor Program, also known as Operation Bracero after the Spanish term for “manual laborer,” funneled Mexicans into the United States on a legal, temporary basis. An estimated 4.6 million Mexicans entered the country legally through the Bracero Program between 1942 and 1964, and states like California soon became dependent on bracero workers. The racial epithet “wetback” was used to describe Mexicans who illegally entered the state of Texas (which had been excluded from the Bracero program because of Texan farmers’ refusal to pay the thirty-cent-an-hour guaranteed wage – about $4.51 in modern dollars) by crossing the Rio Grande River. Even after it declared hiring undocumented workers illegal, the government ignored Texans’ employment of these immigrants. Consequently, hundreds of thousands of Mexican workers crossed the border without permission and found jobs on the farms of employers willing to flout the law.

In another striking parallel to the current moment, Congress attempted and failed to address the problem by instituting employer-sanctions penalizing the growers that hired non-Bracero workers. Frustrated by Congress’ inaction, President Eisenhower decided to address the public’s discontent through the Executive Branch, namely through the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). In 1954, Ike named retired General Joseph M. Swing to implement Operation Wetback, which used military style tactics to seize and deport people en masse. Dragnet style raids took place across the Southwest as well as in Midwestern cities such as Chicago. Many immigrants were shoved into buses, boats and planes and sent to often-unfamiliar parts of Mexico, where they struggled to rebuild their lives. In Chicago, three planes a week were filled with immigrants and flown to Mexico. In Texas, 25 percent of all of the immigrants deported were crammed onto boats later compared to slave ships, while others died of sunstroke, disease, and other causes while in custody. And the Mexican government, which sought to alleviate a labor shortage there, supported the program.

From a media relations perspective, Operation Wetback was a success. The optics of the large-scale apprehensions were powerful and appeased public discontent. A 1955 INS report declared that “the so-called ‘wetback’ problem no longer exists … the border has been secured.” But from a policy perspective, Operation Wetback failed. Soon after, migration from Mexico into the United States picked back up because the core demand for Mexican labor was never addressed. As a result, Operation Wetback ultimately achieved a temporary reduction to a larger migratory flow that leads us to our current immigration context.[2]

Two factors have historically driven unauthorized entry into the United States. The first is a response to the demand by the U.S. private sector for inexpensive labor. Through over 100 years of immigration policy, the previously referenced Bracero program proved to be among the most effective policies the U.S. government has ever established to address this first “pull” factor. According to the Congressional Research Service, “Without question the Bracero program was . . . instrumental in ending the illegal alien problem of the mid-1940’s and 1950’s.” The Bracero program ended in 1964 due primarily to complaints from labor unions. But the demand from the U.S. private sector remained. Thus, until the establishment of legal permits for temporary labor in the 1980’s through the H-2A visa (for farm work), and the H-2B visa (for nonagricultural seasonal work), it was primarily filled through unauthorized workers. Therefore, providing legal pathways to address demographic changes in the U.S (discussed below), and the demand for inexpensive workers in certain sectors must be part of any solution for reducing unauthorized entries. To protect the interests of native U.S. workers, these programs should be limited to sectors for which they have historically shown little appetite, such as agricultural labor and low-level jobs in the hospitality and health care sectors. Like the Bracero program, private sector employers should also be required to provide minimum standards with respect to wages and working conditions. Even with expanded temporary permits, unauthorized entries will continue to fill the unmet demand of U.S. employers and have ebbed and flowed with changes in both the demand for and supply of migrant labor. For example, before then-candidate Trump descended the escalator at Trump Tower, apprehensions of Mexican workers along the Southwest border declined by 82 percent (from 1,106,40 to 186,017) between FY 2005 and FY 2015. What drove this decline was a combination of increased use of H-2A and H-2B visas, reduced demand for construction workers in the U.S., and fewer births in Mexican families in the prior 40 years, which reduced the pool of young men migrating to the United States.

The second factor reflects the historic refugee crisis which has been taking place throughout the Western Hemisphere in response to significant political, environmental, and economic upheaval in countries such as Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti and Nicaragua. This “push” factor began during the Obama administration and has continued to the present day. Even with the more punitive enforcement measures undertaken by the Trump administration, pending asylum cases rose 300% between FY 2016 and FY 2020 (from 163,451 to 614,751), according to Syracuse University’s TRAC. Border Patrol data show that apprehensions on our Southern Border rose over 100% between FY 2016 and FY 2019 (from 408,870 to 851,508). Refugee entry briefly slowed in 2020 due to the global pandemic and the Trump administration’s Title 42 restriction which blocked them from applying for asylum at ports of entry because of the global health emergency. But as pandemic fears subsided, Title 42 health restrictions caused more individuals and families to enter unlawfully by simply turning themselves in to Border Patrol agents to apply for asylum. This drove up “encounters” that fed public outrage over what was seen as an unruly border crisis. Because asylum requests are caused by a complex interplay of dynamics outside of the United States, solutions to address them require a multi-pronged approach which combines increased resources to secure the U.S. border as well as the number of personnel that work on asylum applications, with requiring companies to better screen for immigration status, working with the source countries to reduce their level of privation, and working with border countries to provide for a more orderly review of asylum applications, before entry into the United States. For example, President Biden’s early 2023 “parole” program, which requires asylum seekers to identify a lawful U.S. resident who is willing to sponsor them and undergo a rigorous background check before entry in the U.S., led to a 95 percent reduction in the number of Border Patrol encounters for asylum seekers from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela between December 2022 and March 2023, according to a National Foundation for American Policy analysis. Border Patrol encounters for all other countries not in the parole programs increased by 15% during this period. But for the 2024 election, this fix came too late. By the time it began to yield these results, images of unruly border encounters had hardened the public’s perception that a political change had to be made.

Over the last decade, surging migration has provided a potent opportunity for politicians to scapegoat and stoke fear of rapid changes in society’s makeup.

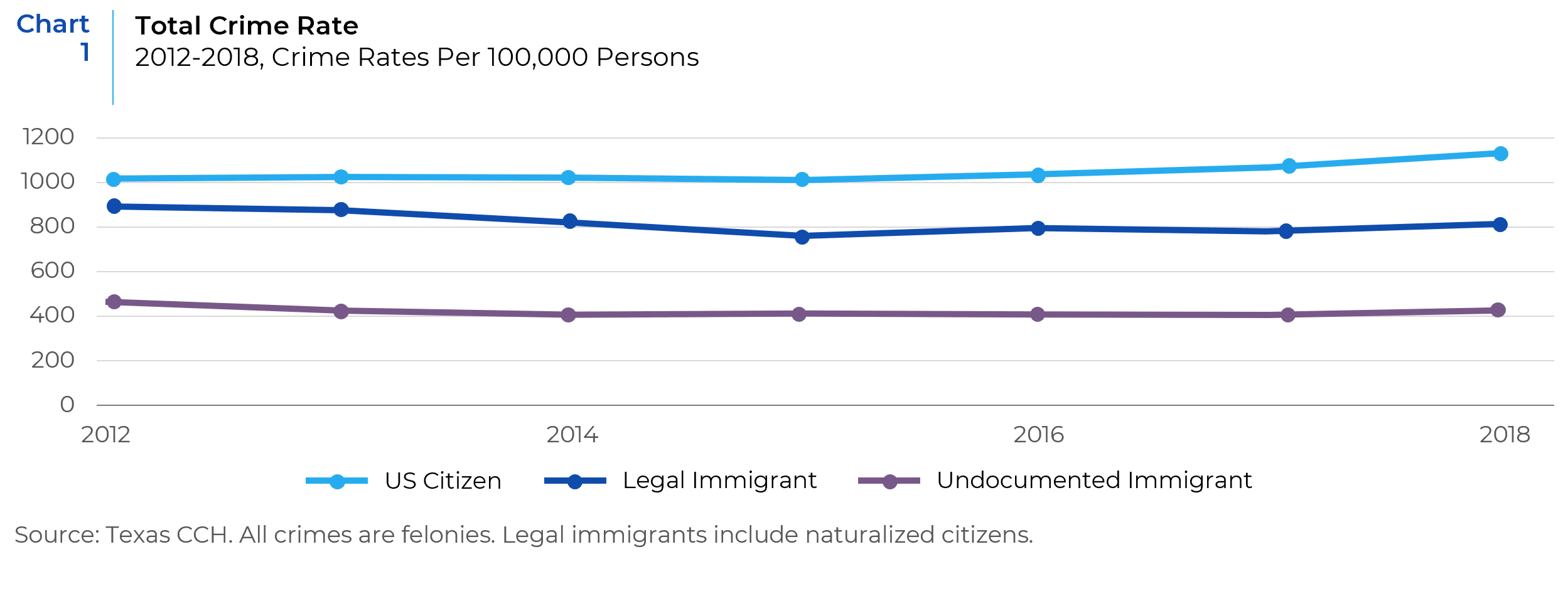

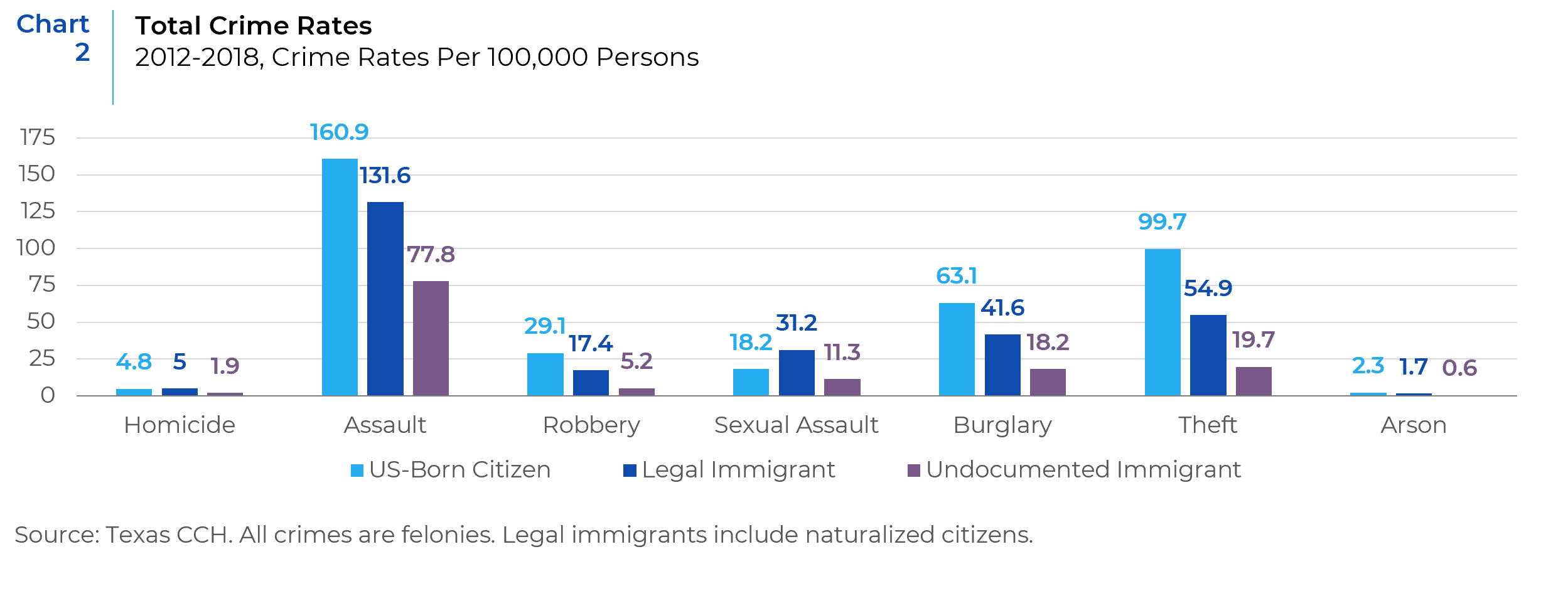

Accordingly, like clockwork, each election bombards us with images of threatening masses of brown-skinned migrants en route to commit all manner of dastardly acts, as well as political commercials that exploit a heinous crime committed by an undocumented immigrant to falsely generalize about all immigrants. But crime statistics show that both documented and undocumented immigrants commit far fewer crimes (across all major categories of felonies) than native born citizens (Charts 1 and 2).

The Immigration in an Age of Decelerating Population Growth in 2020

The age-old and unchallenged stereotype that immigrants are extracting from America’s fiscal largesse at the expense of native-born Americans is also at variance with reality. For one, economic growth depends on labor, capital, and productivity. While technological advances and incentives for investment can contribute to productivity growth, immigration has been vital to propping up labor force growth, because birth rates among American women (1.62 births per woman last year) have been well below replacement level (defined as 2.1 births per woman). Additionally, declining fertility coupled with longer lifespans has profound consequences for the health of economies and government finances. According to the World Health Organization, the growth in the number of seniors has outpaced the availability of care, with a shortage of 10 million health-care workers expected by 2030.

Two-thirds of the world’s population and every industrialized country are grappling with the looming reality of far more deaths than births. Before the end of the century, the United Nations projects that the global population could shrink for the first time since the bubonic plague wiped out as much as half of Europe in the 1300s. The 27 European Union countries that are, collectively, 30 percent below replacement level, are already struggling to keep up with the cost of providing pensions to their swelling ranks of retirees. Further, South Korea, Japan and China (who combined account for one-fifth of the world’s population) expect to halve their populous by 2100. Consequently, both South Korea and Japan have declared their projected population declines as national emergencies.[3]

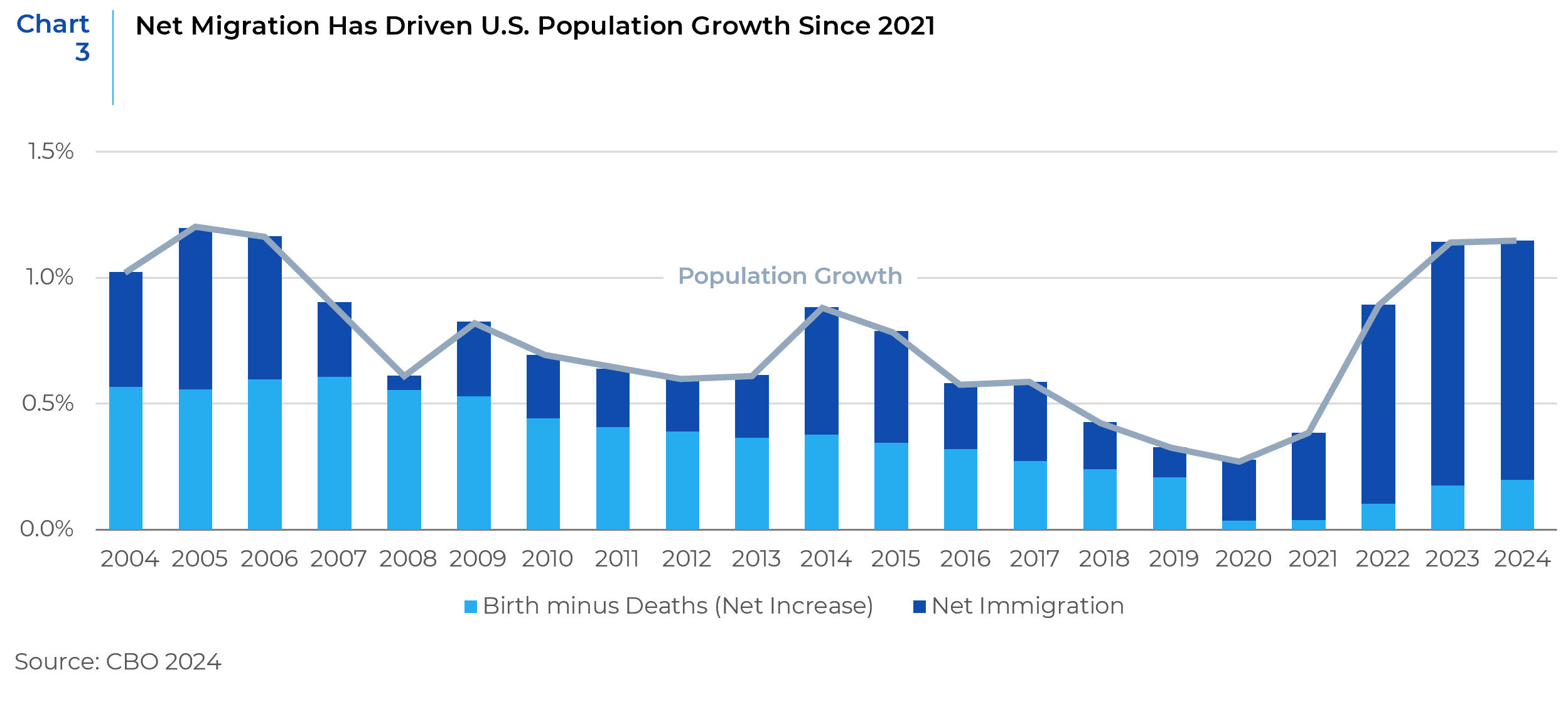

In countries that are facing demographic decline, policies aimed at increasing childbirth have not yet succeeded. In East Asia, for example, cash vouchers and tax credits for parents, plus government subsidies for childcare, have not stemmed their demographic shrinkage. Russia, which had 17 million more deaths than births since the Soviet Union collapsed, has taken a more aggressive approach. Its duma is contemplating a new law against “child-free propaganda,” which criminalizes the spread of information advocating for not having children. America’s “demographic exceptionalism”, despite its dismal fertility rate, owes its’ position to immigration. Increasing the legal immigration quota would continue to cumulatively increase the number of workers and help stem the decline in the worker-retiree ratio. During the post pandemic period, the jump in ready-to-work immigrants boosted population, labor force and job growth.

The economic effects of immigration are complex. As immigrants boost labor supply (which would technically be disinflationary), they also consume goods and services, and thus drive-up aggregate demand (which would technically increase growth and inflation). Their impact also varies with levels of education and skills. Pre-pandemic, immigration was somewhat stable and dominated by legal immigrants that tend to be better educated and more skilled. After the pandemic, encounters of unauthorized migrants at the border surged (Chart 3). This group tends to be less educated working in industries and occupations with lower skill requirements than the native population. Their skills are more likely to complement those of the existing U.S. workforce and they tend to consume a larger fraction of their income than native households. Additionally, a larger workforce increases the return to capital and hence investment. Since the capital stock is slow to adjust, investment initially responds more than output. Particularly for more highly skilled immigrants, this would be expected to generate a small, but positive, inflation response.

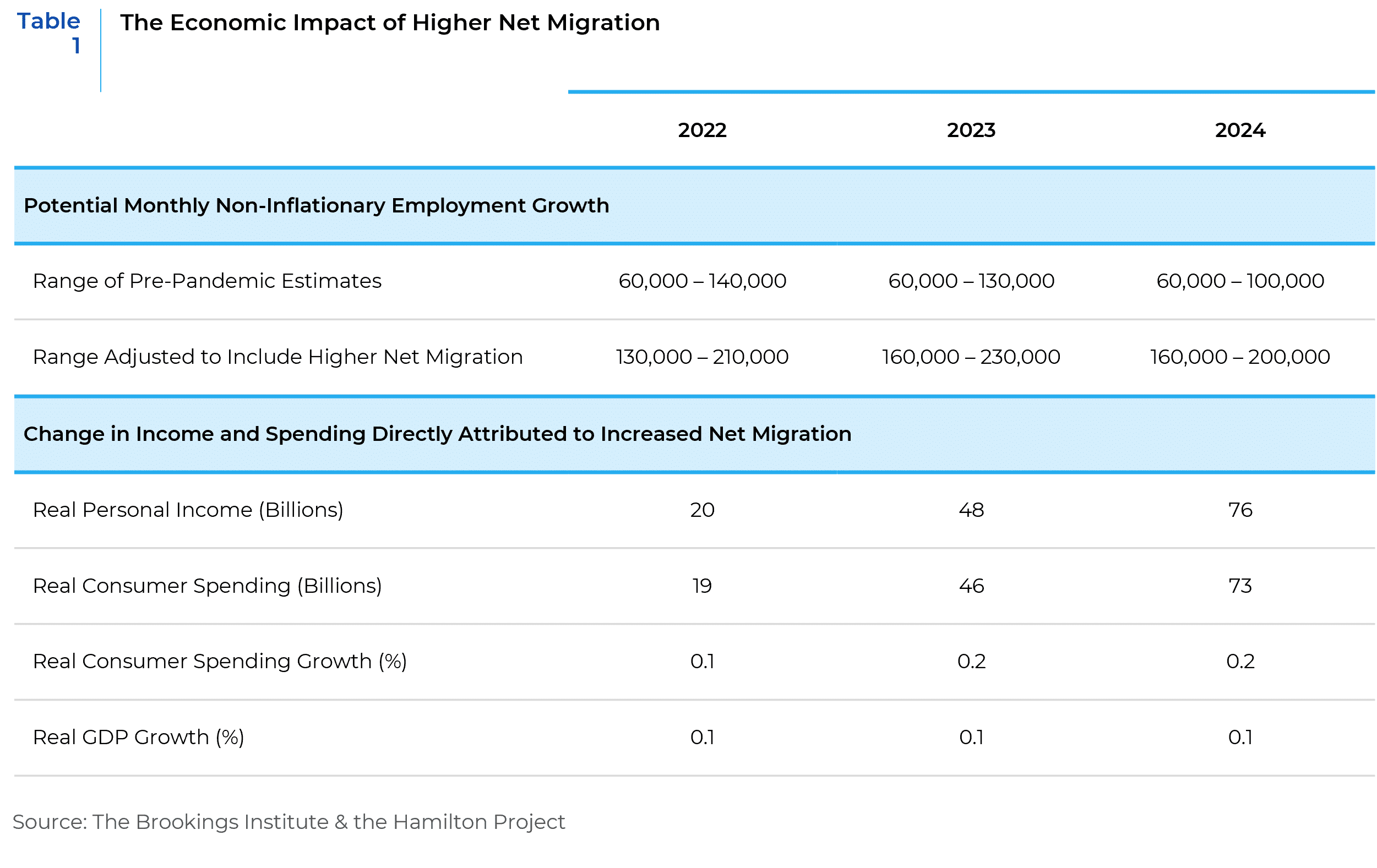

According to the Dallas Federal Reserve, higher immigration rates boosted payroll job growth by 70,000 jobs per month in 2022, by 100,000 jobs per month in 2023 and so far in 2024. Immigrants have not only increased the labor force, but their consumption of goods and services in the United States also bolstered GDP growth. According to the Hamilton Project study, higher immigration has contributed about 0.1 percentage points to GDP growth annually in 2022 and 2023 and is projected to do so again in 2024 (Table 1).

On the campaign trail, President-elect Trump repeatedly promised to implement the “largest domestic deportation program in American history,” which he says would encompass some 10 to 15 million unauthorized immigrants. He has previously pointed to the Eisenhower administration’s mass deportation program where he envisions moving local law enforcement, the National Guard, and the standing army to the US-Mexico border by invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807 to permit the military to arrest unauthorized immigrants. To speed up the pace of deportations, Trump also wants to change ICE deportation procedures, permitting ICE agents to conduct workplace raids rather than exclusively arrest individual people. Similarly, Trump plans to deny due process to unauthorized immigrants as well as suspected members of drug cartels and criminal gangs. To alleviate the burden placed on existing ICE detention facilities, Trump plans to build detention facilities along the border to hold migrants while they await deportation.

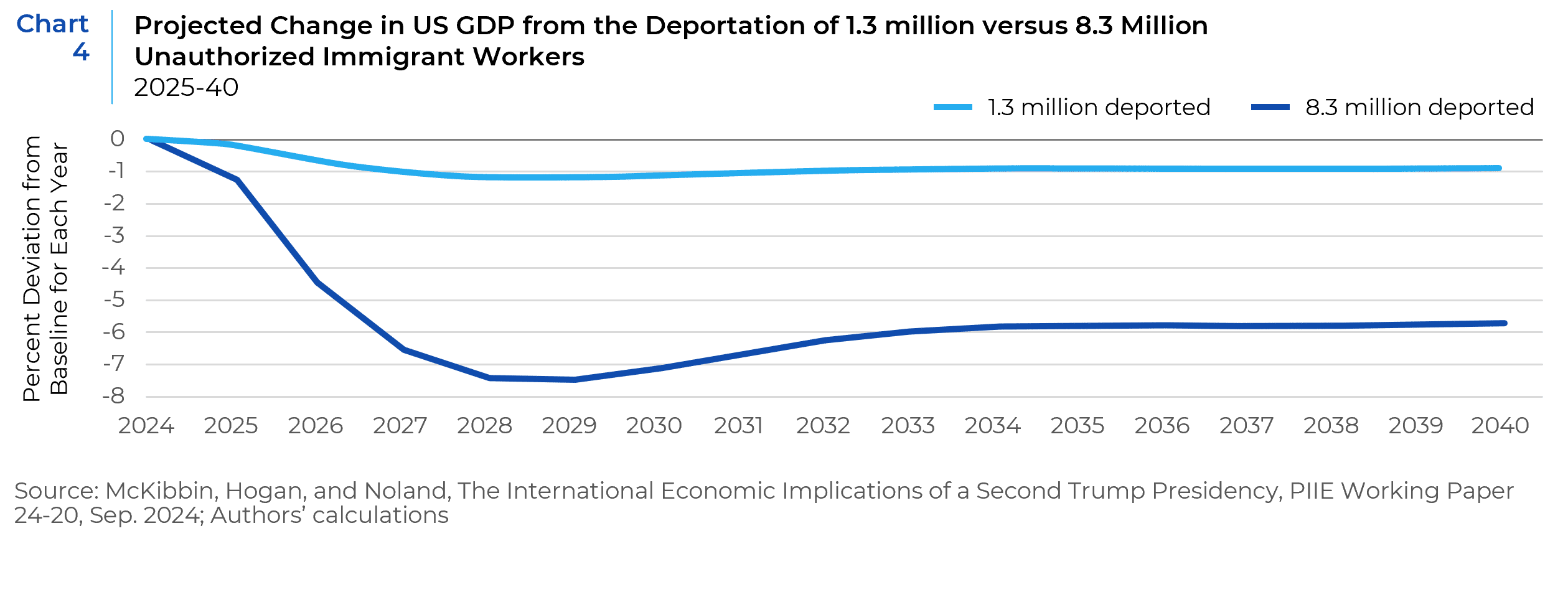

If past is prologue, this strategy could have significant, negative economic consequences. There are an estimated 8.3 million undocumented workers in the United States, which amounts to about 5.1 percent of total employment. According to a study by the Peterson Institute, deportation of all 8.3 million workers would reduce the potential U.S. labor supply by 5.1 percent below the baseline assumed for 2028. If the government deports 1.3 million unauthorized immigrant workers, the potential US labor supply would be reduced by 0.8 percent below the baseline by 2028. A more draconian deportation would cumulatively shave about $5 trillion dollars (or over 6 percent) off the United States’ GDP by 2028. A more measured deportation program of 1.3 million undocumented workers would shave $812 billion (about 1 percent) off the country’s GDP (Chart 4).

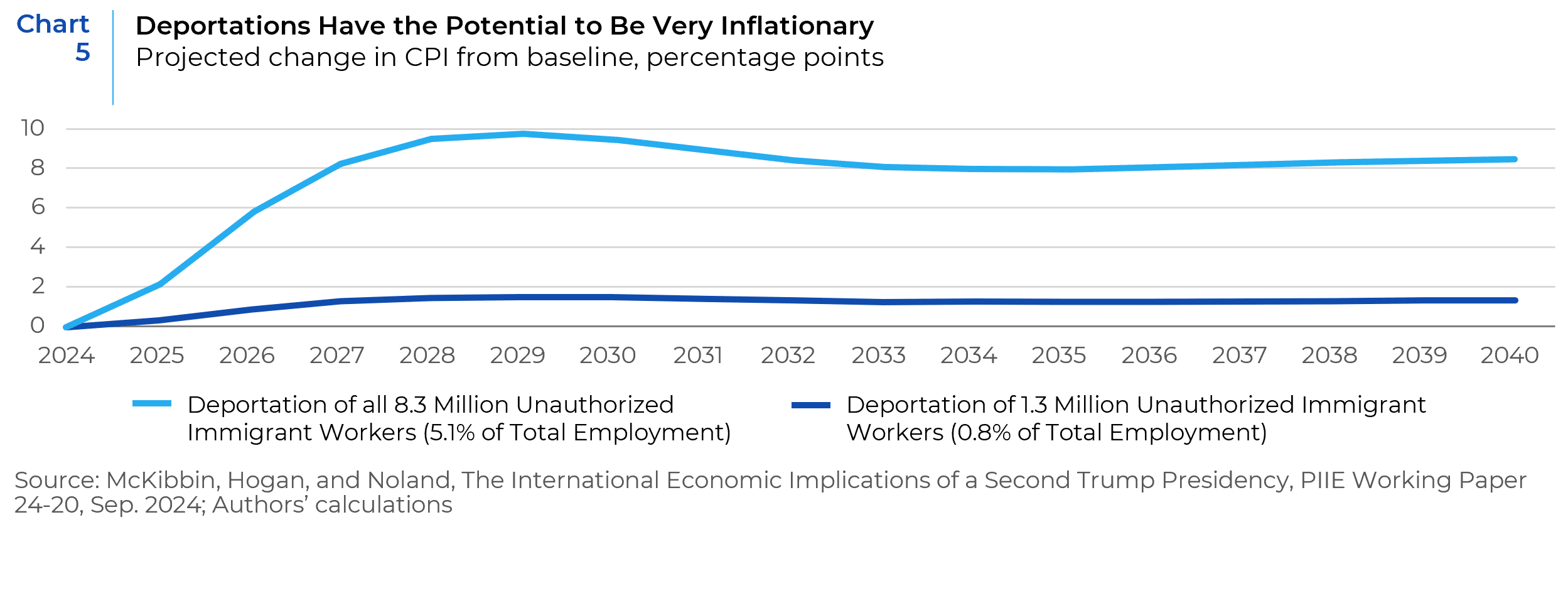

As discussed in Part I of this series, post-pandemic inflation was a major motivator behind 2024’s anti-incumbent movement. Assuming that deportations are focused on lower skilled migrant workers (that tend to complement as opposed to compete with U.S. born workers) and phased in between 2025 and 2026, the Peterson Institute study forecasts a 1.5 percent increase in the Consumer Price Index if 1.3 million undocumented workers are deported. If all 8.3 million undocumented workers are deported, they project a 9.1 percent cumulative increase in inflation by 2028 (Chart 5).

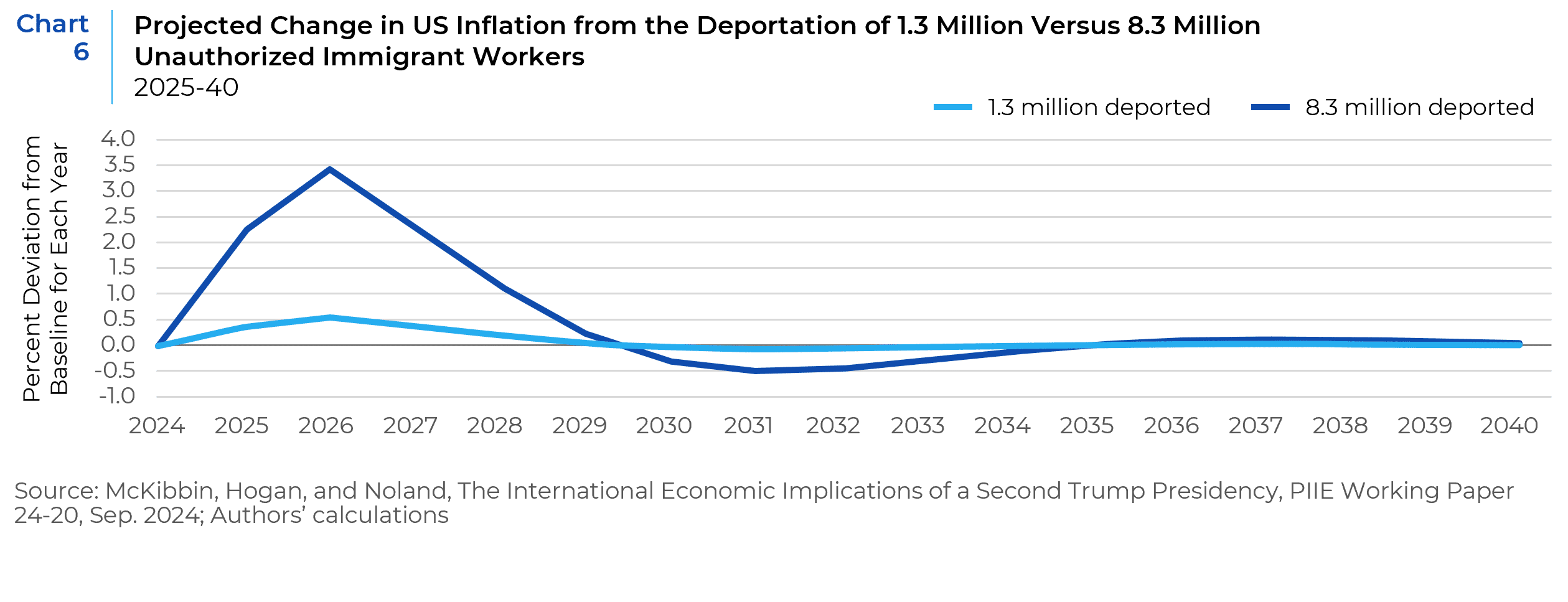

This latter effect, however, is time varying. Because mass deportation would induce a classic supply shock, where prices rise and output falls, the Fed would be expected to balance the slowing economy through policies that contain inflation. After the Fed’s reaction, US inflation is projected to rise by 0.3 percentage point above baseline in 2025 and by 0.54 percentage point in 2026. By 2030, inflation returns to the baseline. Over time, the shock would therefore be mildly inflationary (Chart 6).

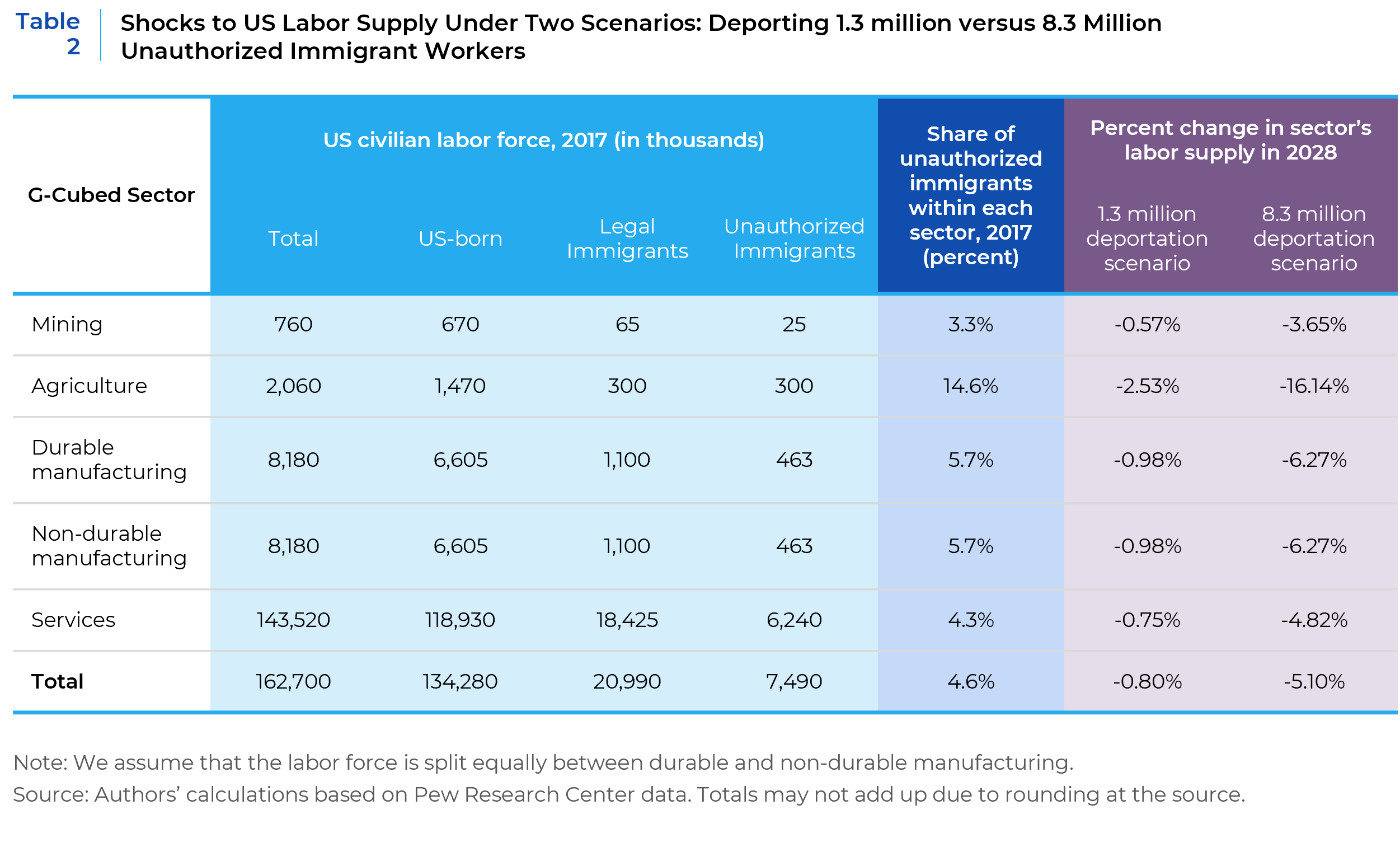

Table 2 contains Pew Center estimates of the number of unauthorized immigrants in the US economy in 2017, divided between six major sectors. While most unauthorized immigrants are employed in the service sector, when measured as a share of a sector’s labor force, their presence is largest in agriculture (for which undocumented workers make up 15 percent of the total workforce), followed by manufacturing (where undocumented workers comprise 6 percent of its workforce). In the U.S., farmers can use the H-2A and H-2B visa programs to legally hire foreign workers. Because U.S. born workers have traditionally been unwilling to work on farms, demand for both programs have grown substantially. The U.S. Labor Department certified 378,000 migrants in 2023, which is three times more than in 2014. Undocumented workers have historically filled most of the unmet demand for farm workers. For example, in California’s heartland, which produces half the fruit and vegetables consumed in the U.S., roughly 50% of the state’s 162,000 farmworkers are undocumented, according to estimates from the federal Department of Labor and research conducted by UC Merced. This is because for decades farmers, and the workers who tend their crops, have engaged in a complicated ballet which uses the plausible deniability of hiring undocumented workers through farm labor contractors. Like their Chinese Five Gangs forebearers, these contractors seek out workers and dispatch them to farms during harvest and planting seasons. Since they require the workers to provide Social Security numbers, they can tell farmers that the workers have valid paperwork. But as reported in a recent L.A. Times article, by the time that they receive notification from the government that the Social Security numbers do not match the names the workers have given, the harvest is over, and the workers are gone.

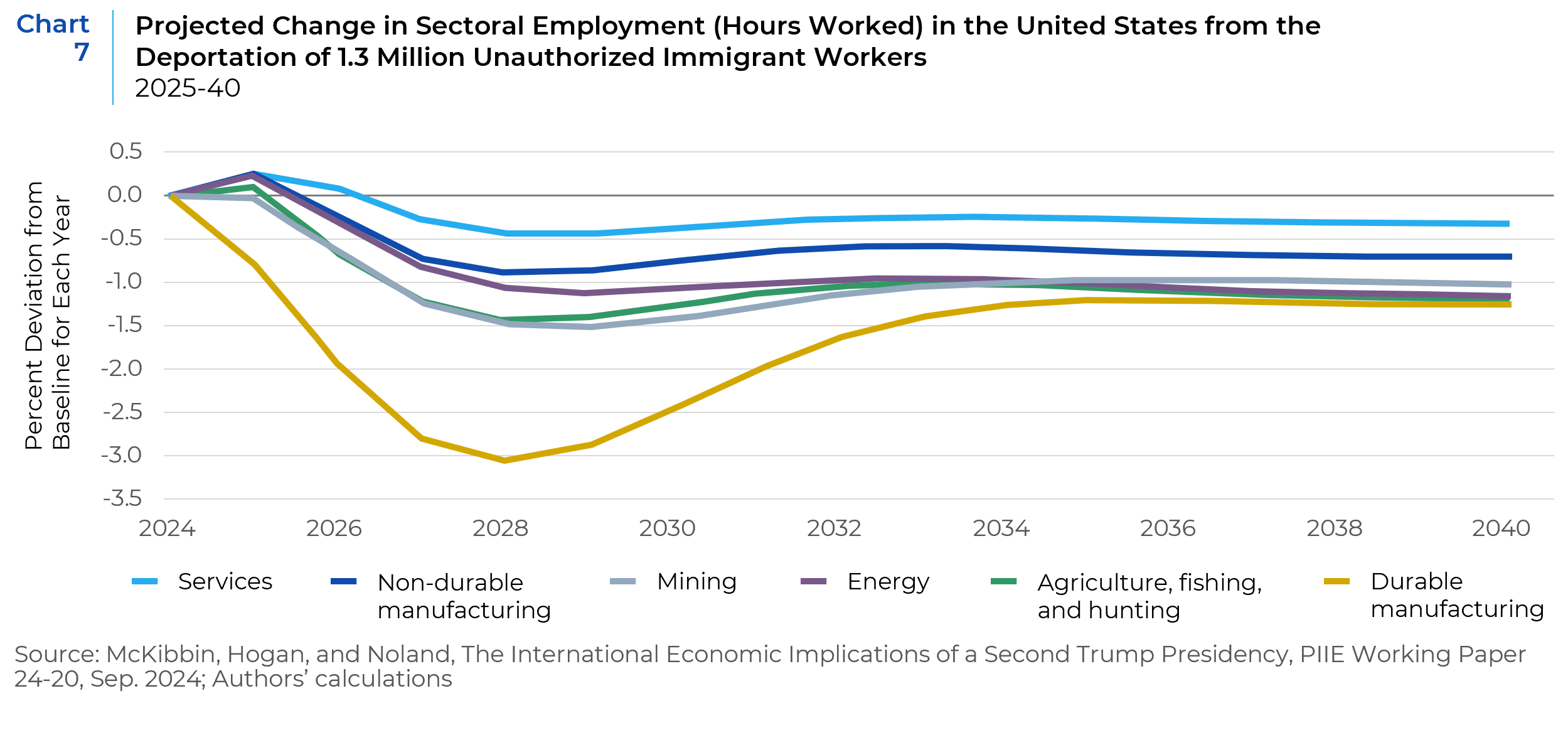

Though undocumented workers make up the largest share of the agriculture sector’s employment, the manufacturing sector is expected to suffer the largest employment and production losses from mass deportation (Chart 7). This is primarily because of an anticipated investment slump across the US economy and lower demand for manufactured goods used in production. Employment in durable manufacturing would take the biggest hit, with hours worked 3 percent below baseline by 2028 due to the slump in investment. Additionally, sectors exposed to international trade (agriculture and mining) would have higher labor input costs and, therefore, become less competitive. This is offset slightly in world markets due to an anticipated depreciation of the US dollar.

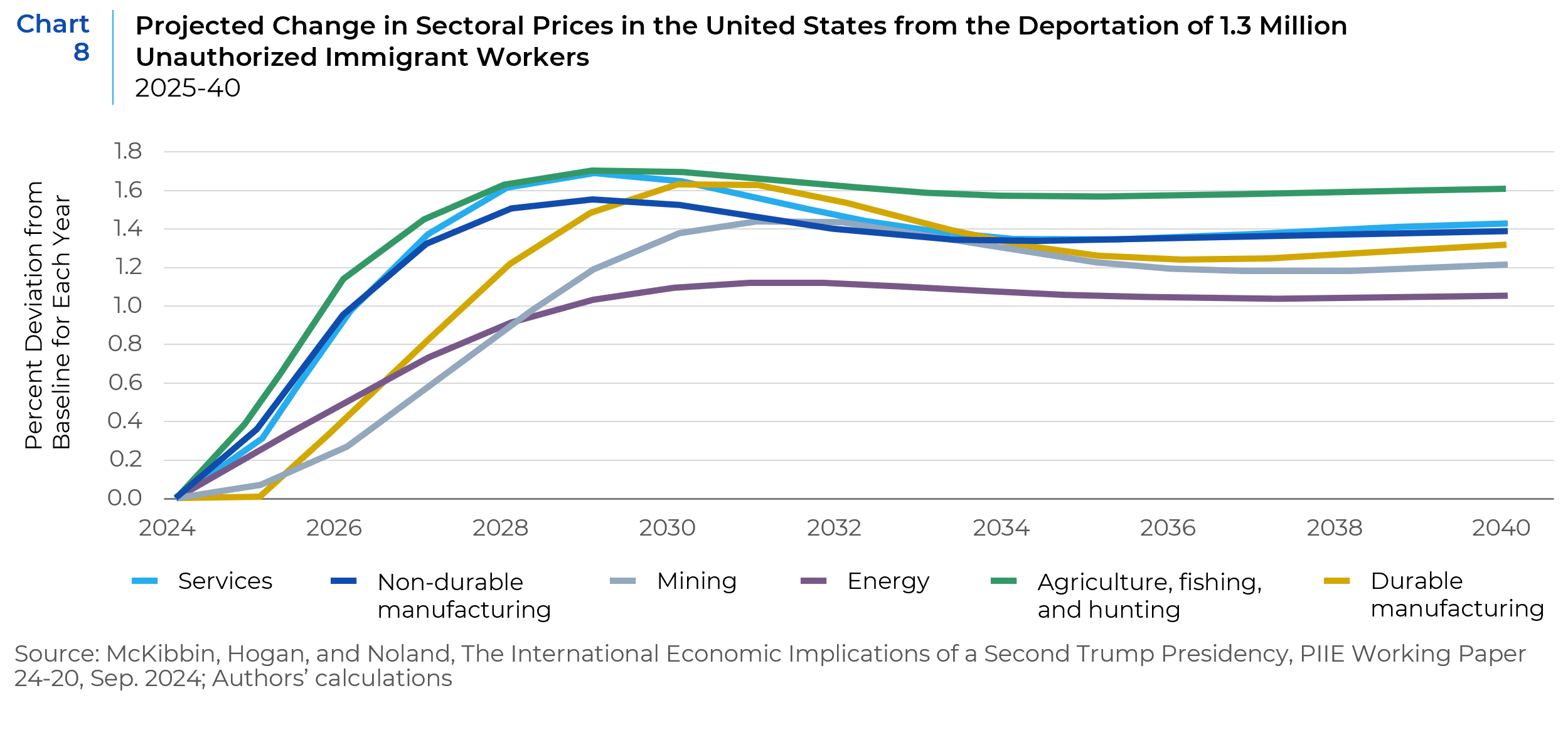

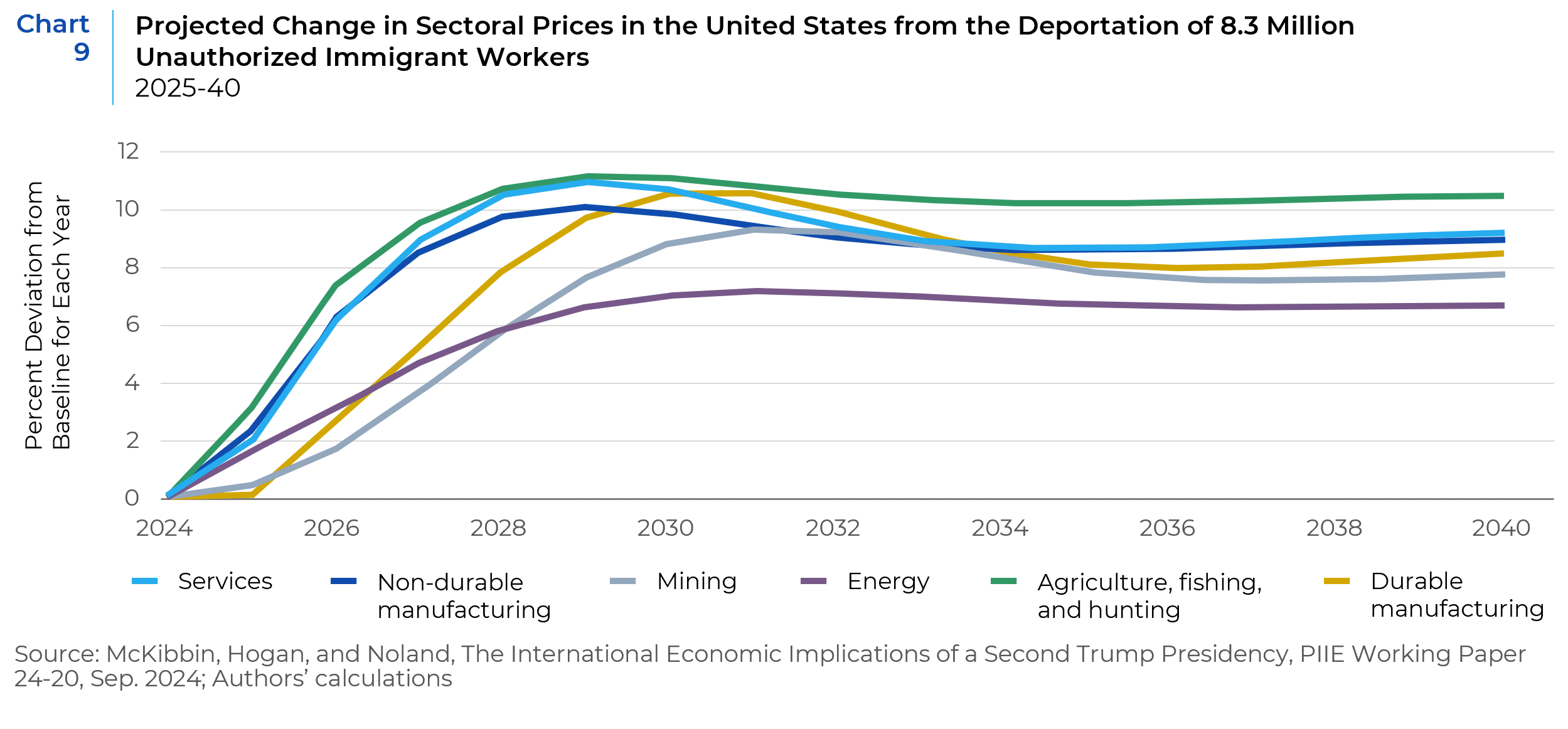

The Peterson Institute study projects that the agricultural, fishing and hunting sector would be the largest driver of the higher inflation caused by mass deportation of undocumented workers (Charts 8 and 9). Most of the increase attributable to this sector would be transmitted through higher prices due to lower food production, as deporting 1.3 million unauthorized workers would reduce the agricultural workforce by 2.5 percent without sufficient substitution from U.S. workers. If all 8.3 million unauthorized immigrant workers were deported, the scale of the adjustment would be over six times larger.

Conclusions

It is important to note that even if immigration is beneficial at the aggregate macroeconomic level, low-skilled native workers may not see a translation in discernable “quality of life” benefits as immigrants may compete with them for low-skill jobs. While this series refers to “low-skilled workers/jobs” a better term may be “low-wage workers/jobs”. While these jobs do not require years of training and/or education, they do require skills and experience. They are vital to the U.S. economy (hence the constant demand for labor, whether native born or immigrant); however, generally these jobs do not pay a living wage. In sectors where these workers are concentrated (such as food services, hospitality, health care and construction), the availability of low-cost immigrant labor can suppress wage growth and reduce job opportunities for U.S. citizens. From the perspective of a low-skilled native worker, aggregate economic gains in GDP, labor participation, and productivity ring hollow when juxtaposed with the immediate pressures of job competition and stagnant wages. For these individuals, the costs of high immigration are not offset by abstract macroeconomic gains, creating a pervasive sense of economic exclusion which naturally fosters discontent. When immigrant workers compete with these same workers for scarce goods such as low-cost housing, this discontent worsens.

Scapegoating immigrants and mass deportations provide a politically expedient opportunity to satiate voter discontent. However, they have not provided a durable solution to private sector demand for inexpensive labor. Moreover, in a rapidly changing economy, whether the change comes from trade, immigration, or technology, mass deportations (or tariffs) will not truly improve the economic prosperity of the working class without a domestic policy that guarantees a minimum living wage, and provides for lifelong learning and skills retraining, to ensure opportunities for native workers and communities.

In Part III, I evaluate the main tenets of incoming administration’s trade and fiscal policies. In this final paper, our investment teams will also evaluate the investment implications of these policies.

[1] The “Six Companies” were officially named the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. This consortium of six California-based Chinese organizations was active from the 1850s to 1882, supporting and advocating for the immigrant community in the West and nationwide. (U.S. Department of the Interior, The Chinese Six Companies (U.S. National Park Service), National Parks Service)

[2] “The Bracero Program: 1942-1964”, Colorado Oral History & Migratory Labor Project, University of Northern Colorado, The Bracero Program

[3] UN World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results: World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results | DESA Publications

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.