The great American stimulus of the summer of 2023 will now extend to 16 countries worldwide in 2024 before disseminating a last sprinkling of economic largesse in the U.S. just in time for the 2024 presidential election. Already responsible for an estimated $5 billion in stimulative consumer spending – the equivalent of the entire annual earnings of Starbucks, American Airlines, or FedEx – the Taylor Swift ‘Eras’ Tour is doing more than its part to save the global economy. However, the economic phenomenon being dubbed ‘Swiftonomics’ will forsake China, as the pop legend’s tour plays four dates in Japan and a record six dates in Singapore, but not in the world’s second largest economy. That the pop queen of hard breakups is snubbing China (and likely will draw substantial money out of China with her dates in neighboring markets) is fitting as the relationship between America and China is also on the rocks. For investors, the separation may just be beginning. Amid the “The Great Rebalancing” between asset classes we wrote about in our Q1 outlook, we believe that long-term investors should also be considering changes within asset classes, among which is a strong case for segmenting how Chinese risk assets (mostly listed equities) are managed. We also recommend that institutional investors carve out the bulk of their China risk exposure from otherwise global and/or global emerging market portfolios and replace it with dedicated China mandates managed by active, nimble absolute return-oriented specialist managers. As emphasized in previous research notes, passive or smart-beta exposure to China is fraught with risks, and should be abandoned altogether.

“It’s Me, Hi, I’m the Problem, It’s Me”1

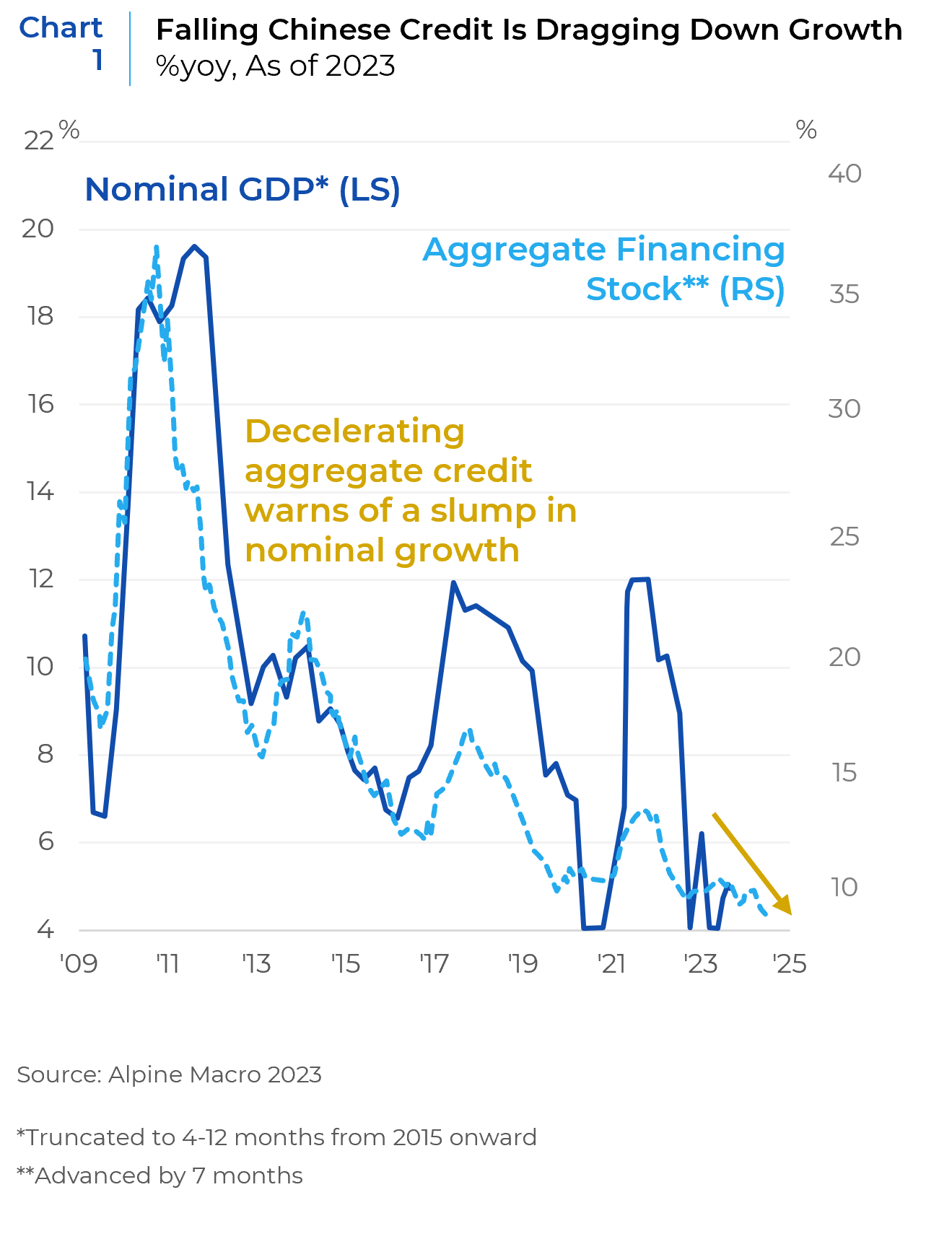

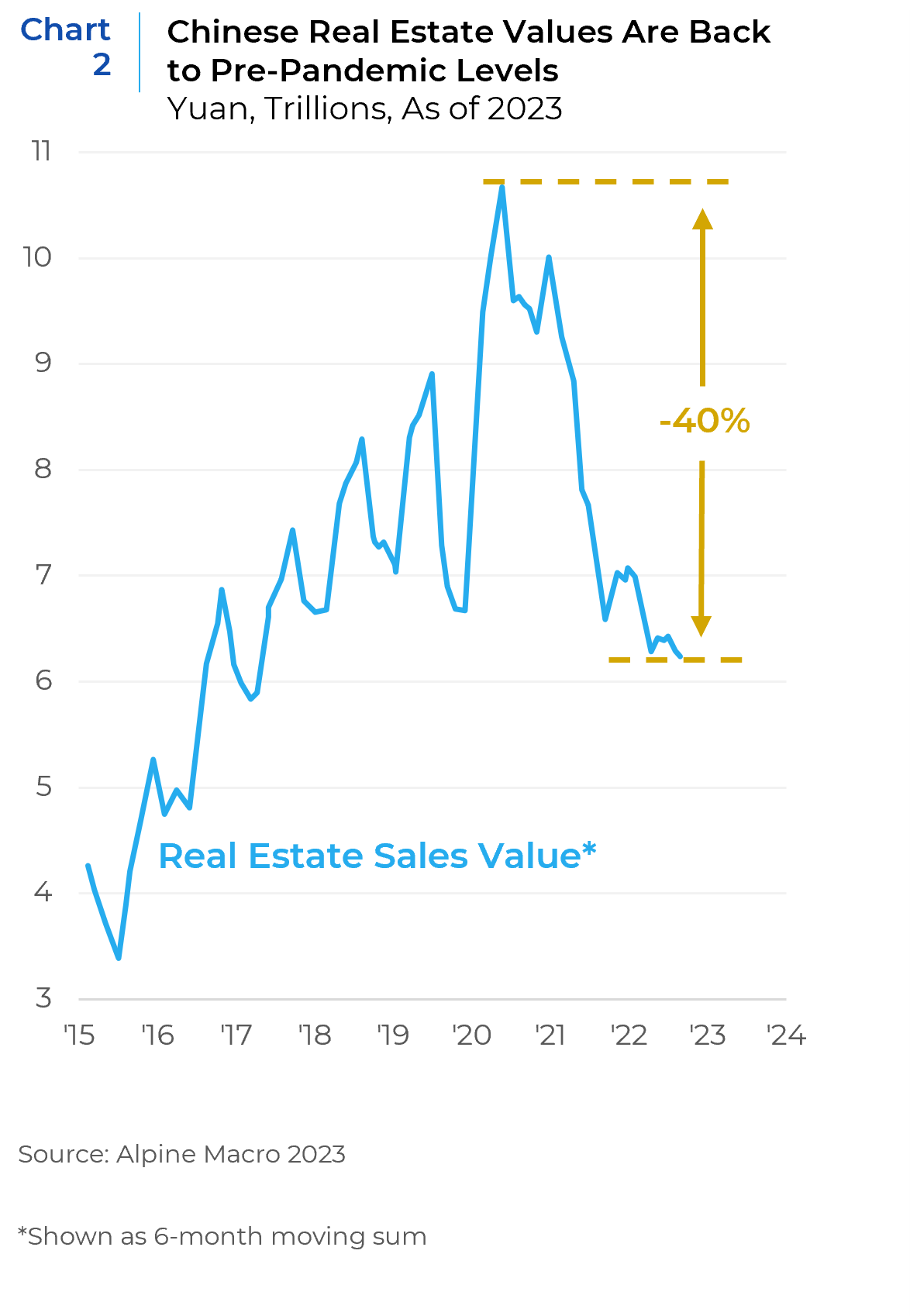

The discussion of Chinese markets is already a well-trodden topic as the Chinese economy is by most accounts at its worst point in the past 20 years. A collapse in credit conditions (Chart 1) has caused (or has accompanied, depending on which economist you ask) a massive collapse in real estate prices (Chart 2), which has combined with generally decelerating growth, the government led disruptions of private sector confidence that began in the summer of 2021, and a post-pandemic malaise which has profoundly shaken consumer confidence.

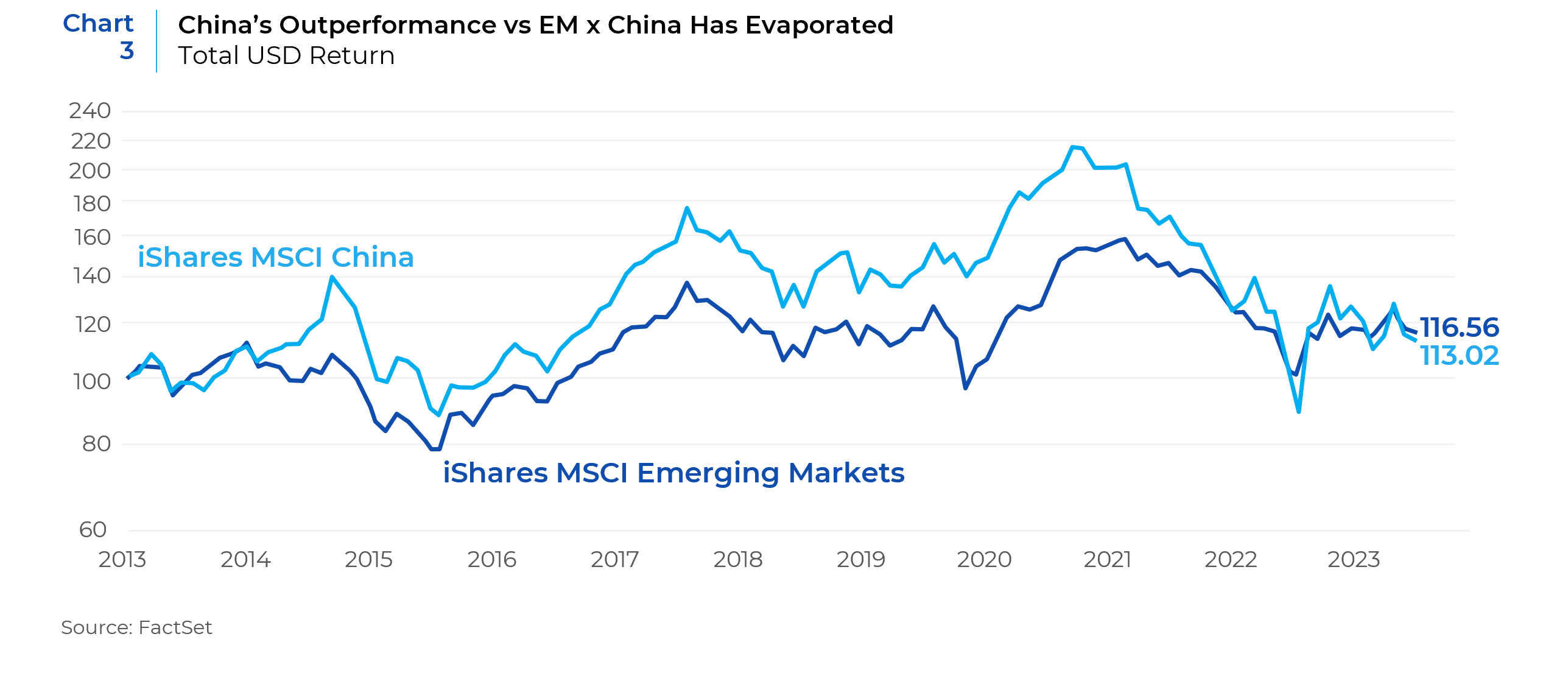

China’s internationally accessible equity market is down 45% from its mid-pandemic highs (Chart 3), erasing all the equity value accumulated since 2017 when Alibaba, Tencent and the other Chinese internet giants became ubiquitous in investors’ portfolios globally. Based on consensus earnings estimates, the market is trading at its largest discount to the rest of the emerging market universe since 2015 (Chart 4).

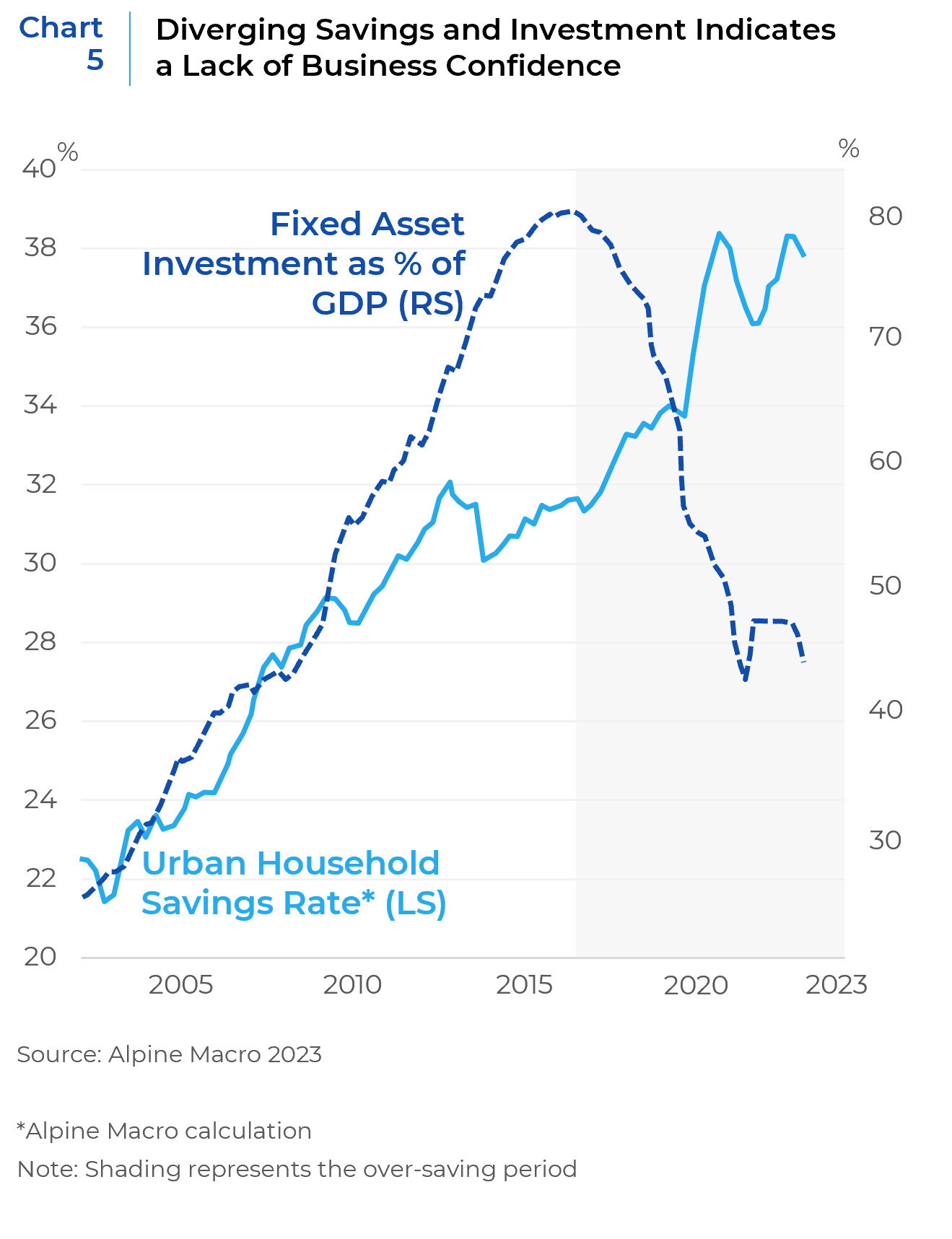

A massive surge in Chinese savings amid a substantial decline in investment speaks to a loss of confidence among consumers and businesses alike (Chart 5). And while Chinese consumer survey data lacks the history and accuracy of other major economy equivalents, nearly all available anecdotes from independent sources tell stories that increasingly point to long-term changes in Chinese consumer and business behavior that could extend well beyond the current economic cycle. Despite an estimated 3% growth in 2022 and a forecast in the range of 2-4% (which would be the envy of most U.S., Japanese, or European policymakers), this is the weakest period of economic growth for China since Mao Zedong’s ill-fated Cultural Revolution in the mid-1970s. Before the pandemic, the mood in China was ebullient and a generation of Chinese millennials knew nothing but 10-15% wage growth every year of their lives, even through the GFC when the rest of the world was experiencing its own hard landing.

China’s economy can, and likely will, continue to grind out positive aggregate growth given the tools at the disposal of Chinese policymakers to stimulate at will. This leaves the level and timing of a Chinese market rebound with a vast degree of uncertainty. At Xponance we also do not have a clear view on these questions of level or timing. Where we are much more strongly convicted, however, is that the underlying drivers of change in China (and thus the investible opportunities within risk assets) will continue to be structurally divergent from the rest of the world for a long enough period of time to justify the segmentation of Chinese equities within a portfolio.

“I’m alone, on my own, and that’s all I know”2

For some, the groundwork for this structural shift in managing Chinese investments has been in the cards for years. In August 2017, we laid out the case for segmenting China within emerging market portfolios based on the (then) growing size of the market and its own already-present idiosyncrasies.

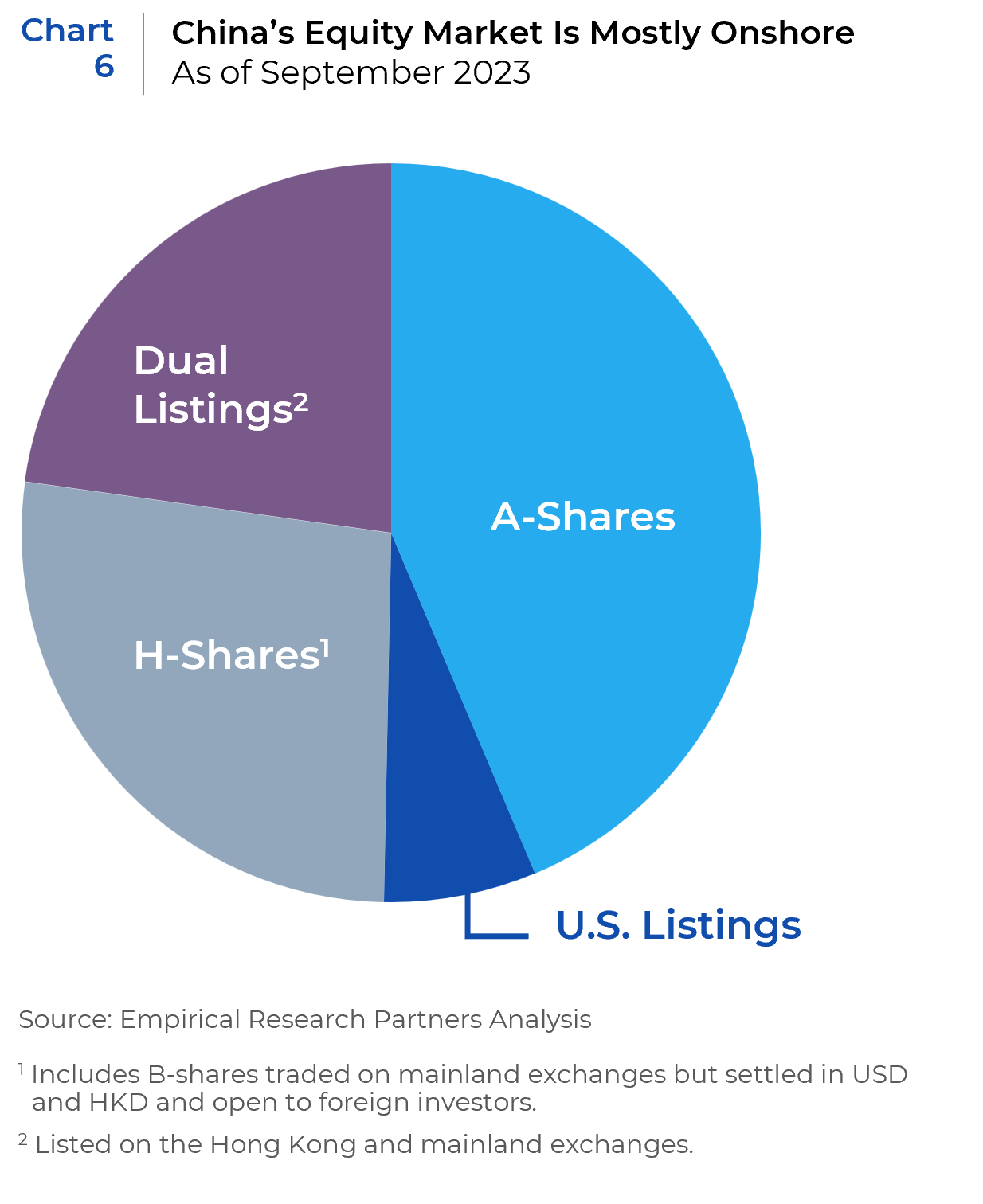

As a reminder, Chinese stocks are divided into those listed in Hong Kong and in China, as well as a smattering of listings in the U.S. and Singapore. By far the largest part of that market (see Chart 6) are those listed onshore in China. These onshore stocks are in turn divided across two exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen, the bulk of which are dubbed ‘A-shares’. Until 2014, access to Chinese A-shares was tightly limited to large global investors via a quota system, effectively closing off the market to all but the very largest international investors. Since 2014, access to the Chinese A-share market has been gradually liberalized via the introduction of the “Stock Connect” programs between Hong Kong and Shanghai and Shenzhen. But only with the most recent expansion in March 2023, which added another 1,000 companies to the program and bringing the total number of A-share companies available to international investors up to over 3,600, is the nearly full investible breadth of the market available to international investors.3 But while the bulk of the market is now accessible, Beijing still maintains quotas on the amount of daily trading via this program. Consequently, while foreign investors own more than a third of the Hong Kong-listed issues, they account for a mere 3-5% of issues listed in Shanghai and other onshore markets.

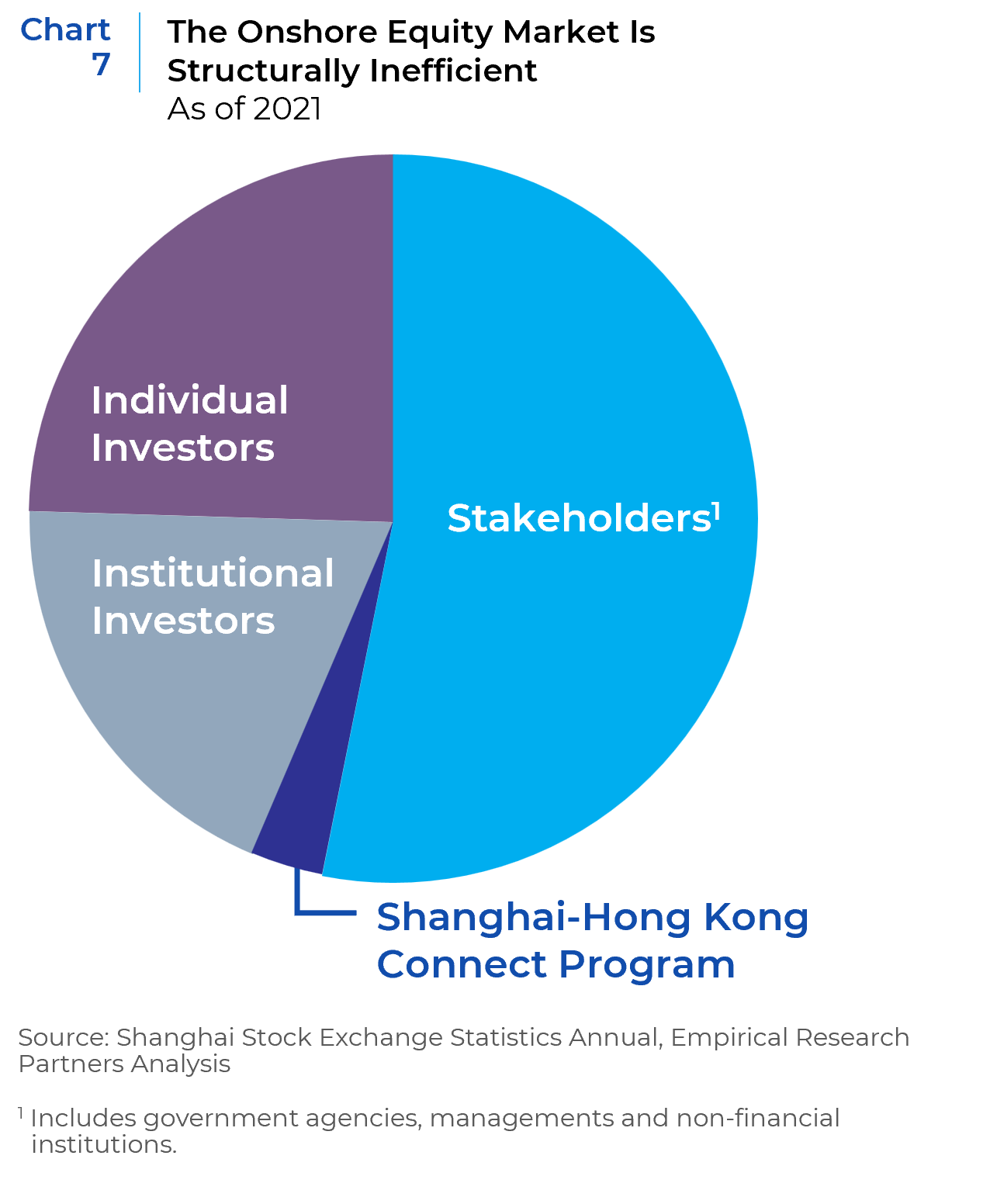

Within the A-share market, only about half of the capitalization of the A-share market floats and roughly half of that is held by retail investors (see Chart 7), more than double the retail share in the U.S. This leads to extremely different market behavior. This has almost always been true. Traditional equity factors that add value in non-Chinese markets, or even other emerging markets in Asia, are ineffective in China. Fundamental managers have long reported on wide differences between local Chinese stocks and global or regional norms in critical areas such as corporate investor relations, analyst coverage, and even balance sheet analysis, not to mention widely divergent market technicals and valuations.

“So let me go my own way, opposite from you”4

Since the pandemic, these differences have grown even wider. China’s early entry and initial exit from the pandemic and subsequent re-entry and draconian lockdowns alongside the forced deleveraging of the property market have increasingly put China on an economic island. But the most pivotal change has been the increased scrutiny of the state over the Chinese private sector amid an historic concentration of power in current Chinese President Xi Jinping and a re-writing of the social contract in China. Beginning with effectively blocking the ANT Financial IPO in late 2020, the Chinese state began to insert itself in areas it had previously tread lightly. The de-legalization of the lucrative private tutoring business in the summer of 2021, alongside further insertions of the Chinese state into its then-booming e-commerce sector, caused local and foreign investors to materially recalibrate their risk and financial models. The market hit bottom over the Halloween weekend in October 2022 as President Xi consolidated power even more than most observers expected, prompting many investors to exit China entirely.

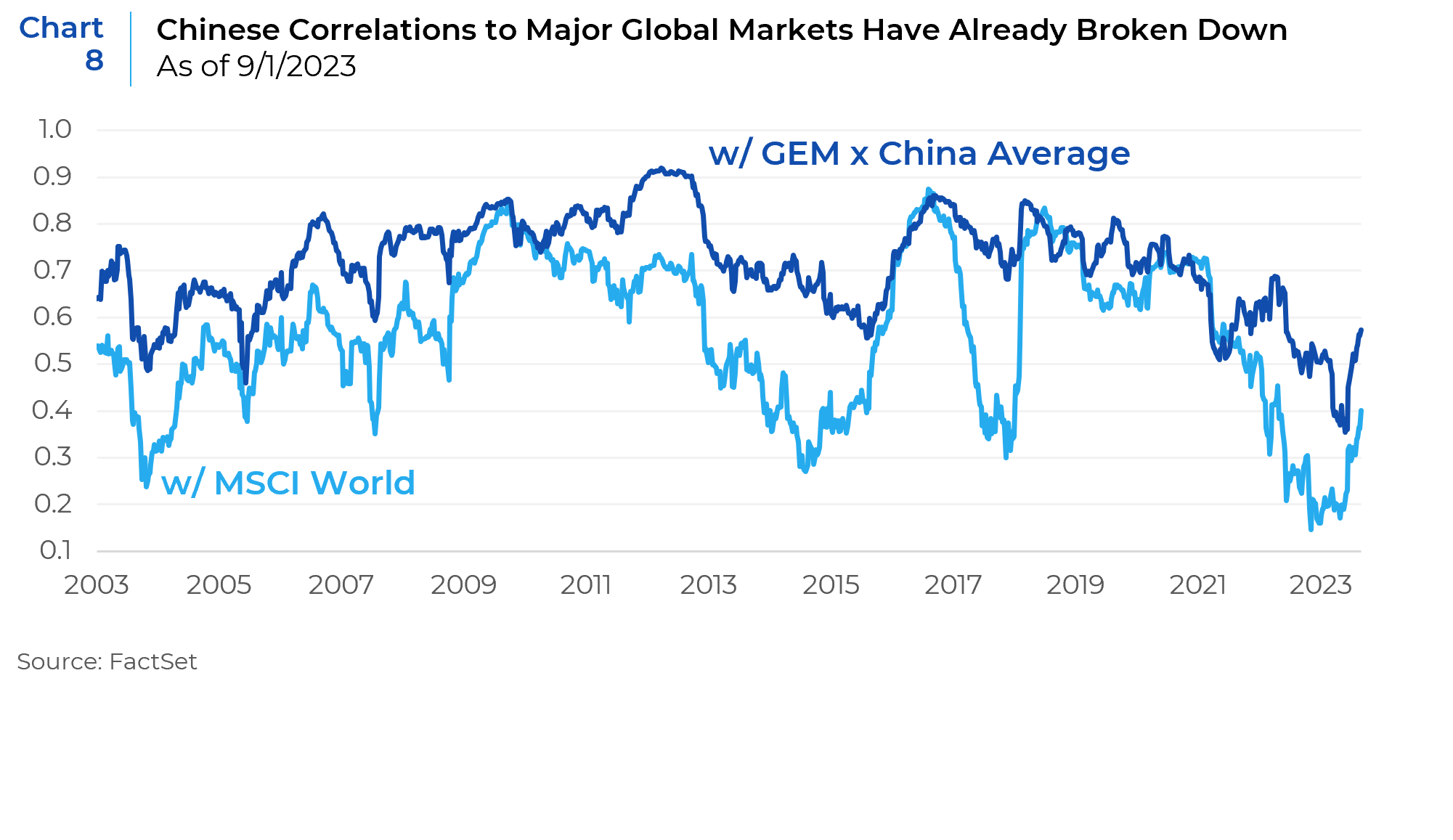

While we think that investors may have overreacted, it is undeniable that China’s political economy is now even more unlike any other major economy. But China also continues to change faster than most. In just the past few years, successive waves of Chinese policy have pushed material transformations into major areas of the economy ranging from banking, insurance, property, utilities, autos, and mining. Meanwhile innovations and changing consumer preferences have radically altered local consumer spending habits on top of the accelerated adoption of e-commerce, mobile payments, and other changes seen globally over the past few years. The divergence in market behavior has resulted in a sharp decline in correlations with the rest of the world’s major markets, including other emerging markets (see Chart 8).

Just this year, China has seen substantial changes in government policy regarding data security, credit, and residency rules in several major cities that have direct and material effects on the earnings potential of companies.

While China’s position as a highly regulated economy experiencing substantial structural changes is unique, there are parallels in existing markets for how to handle such circumstances. Global investors know from experience that the more highly regulated the industry, and the more uncertainty there is in the regulations, the more dispersion there is in returns. Diverse alpha availability is typically best navigated through a specialized focus. In the U.S. market, highly regulated sectors, such as biotech, healthcare, and banking, have spawned a cottage industry of sector focused funds. The same logic now applies to China, but where the whole market is highly regulated and where the opacity and uncertainty in the regulations is uniquely high.

“I’m the only one of me, baby, that’s the fun of me”5

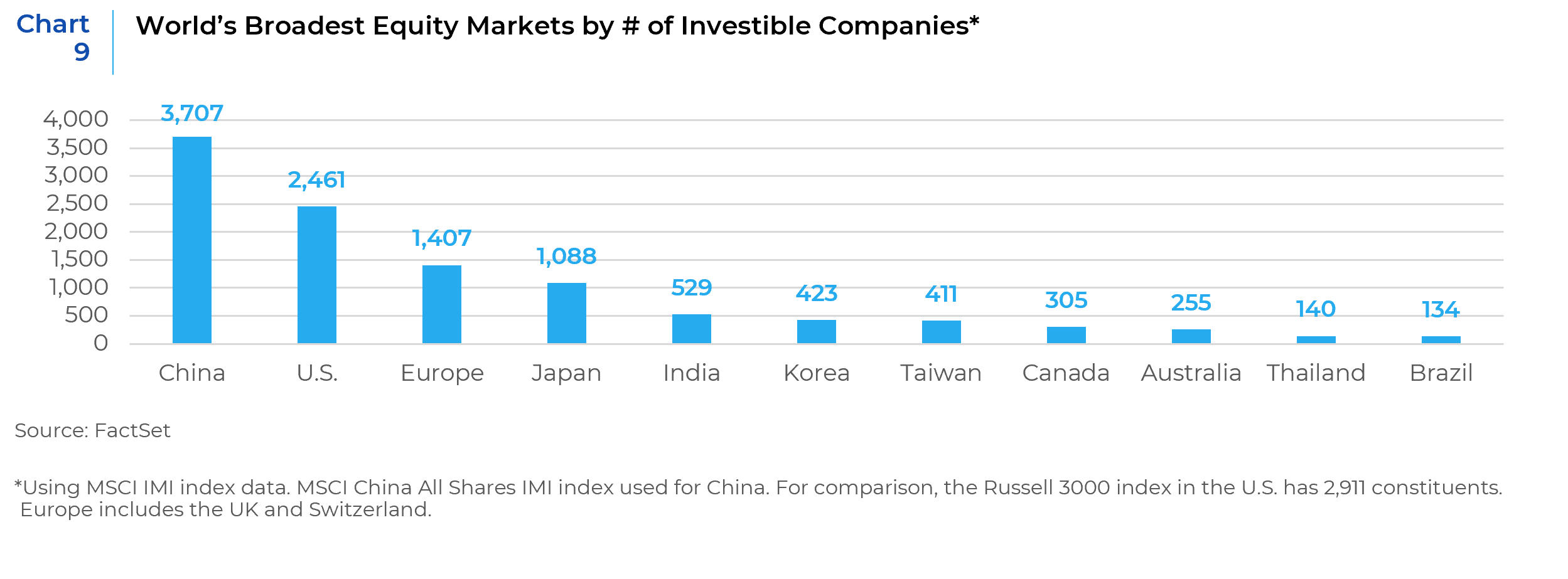

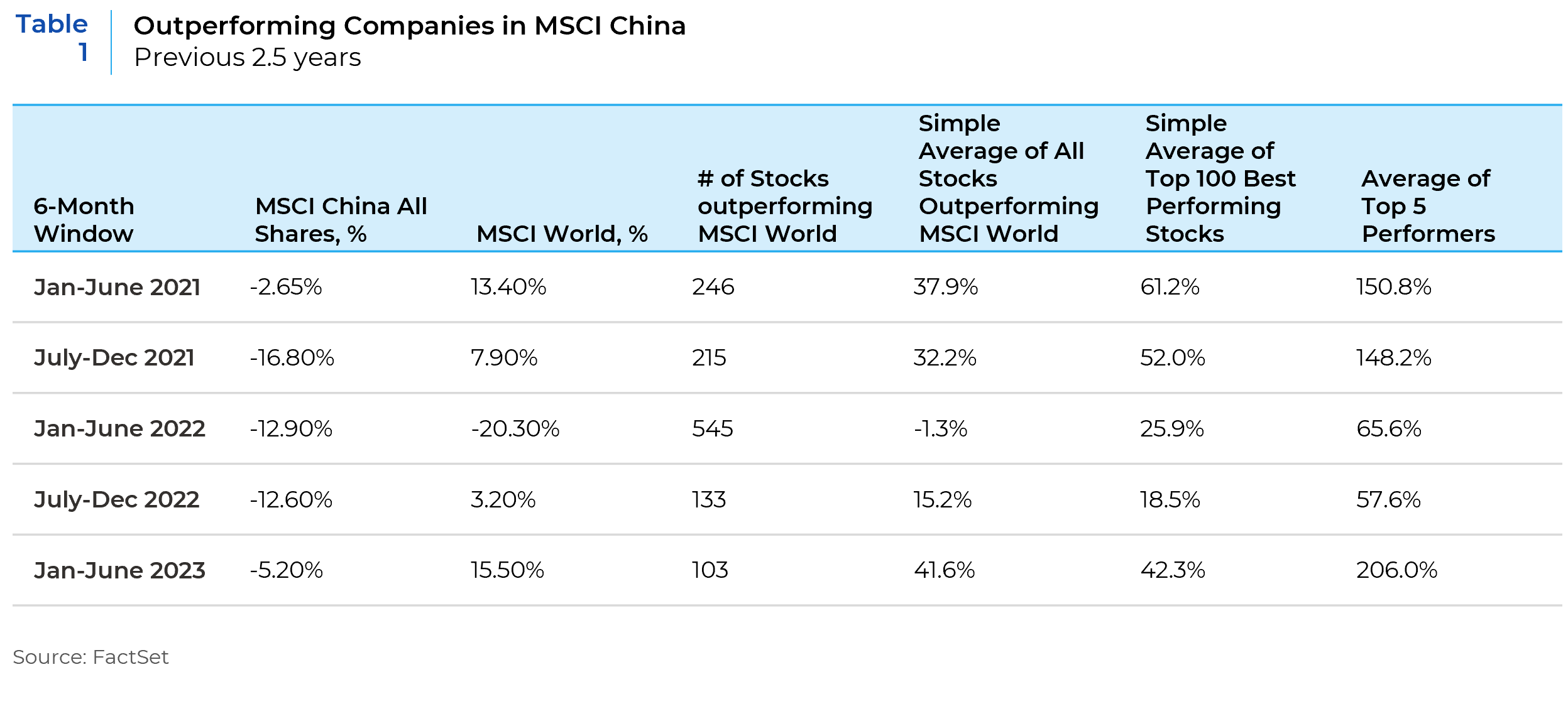

Given the uncertainty in China, it would be tempting to simply dismiss the market as not worth the effort to maintain further investments there. We believe this too is an overly simplistic response. As with the United States, in an economy as massive and dynamic as China’s, there will always be pockets of strong growth and/or fallen angels that nimble active investors can find. With over 3,700 investible stocks, China is the broadest equity market on the planet (see Chart 9). As such, even in its worst bear markets, it remains a rich hunting ground for an actively managed portfolio of companies with strong returns and low correlations to other global markets. Indeed, throughout this recent prolonged bear market in China since the end of 2020, there has continued to be a rich subset of outperforming companies during each six-month period over the past 2.5 years, just within the much smaller (roughly 800 constituents) mid-large cap MSCI China All Shares index (see Table 1).

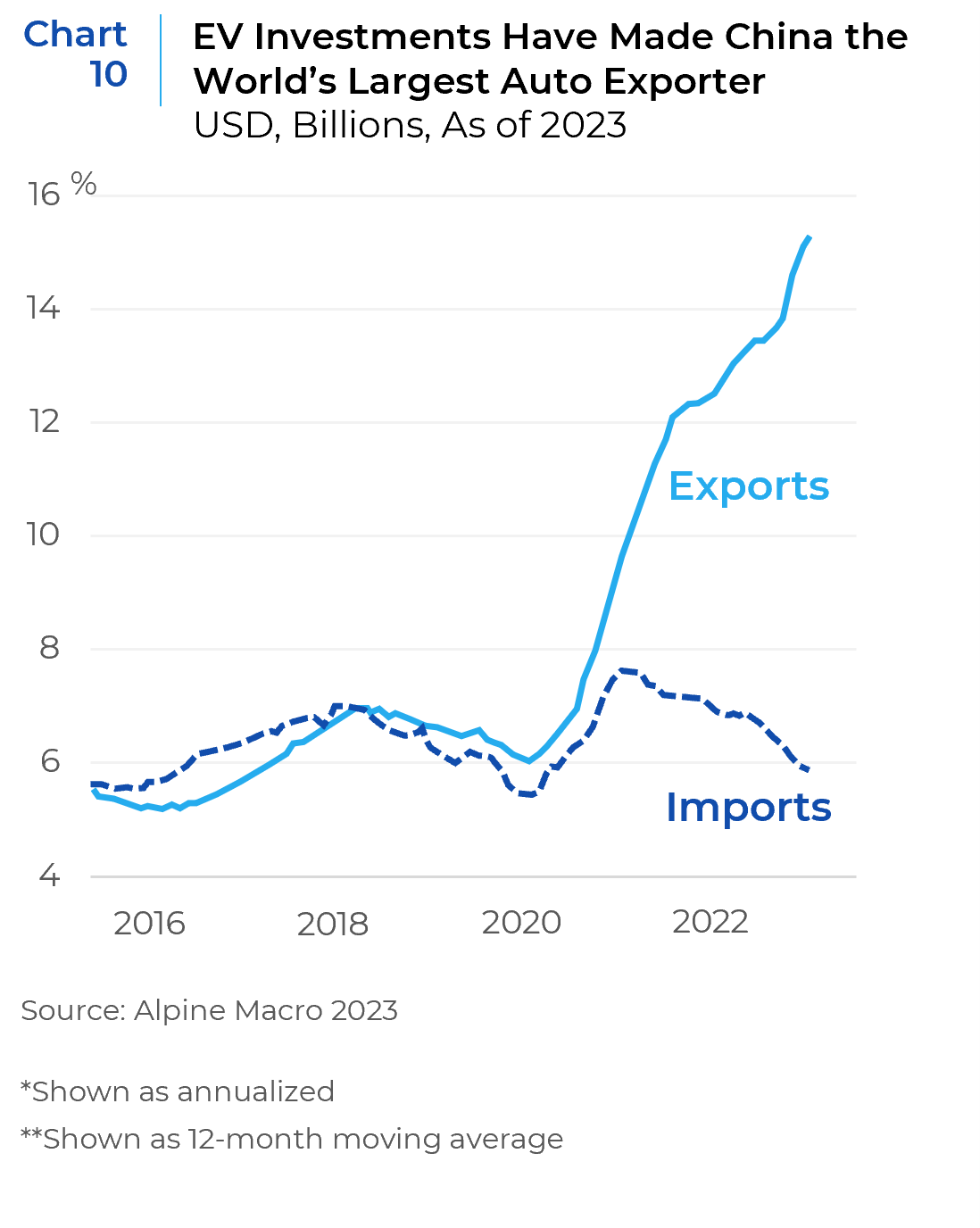

One area of massive growth in China through this bear market has been auto sales (see Chart 10), where China has grabbed first mover advantage in EV sales across Asia and other foreign markets and this year overtook Japan to become the world’s largest exporter of autos. The explosive growth in EV manufacturing is the direct result of favorable state policy, in the same way that prior episodes saw huge growth in construction/infrastructure, mining, solar panel manufacturing, as well as the ongoing promotion of the semiconductor industry.

“We are never, ever, ever getting back together”6

We are already seeing a move among investors towards segmenting Chinese assets from their portfolio allocations, particularly within emerging markets, where Chinese equities remain approximately 30% of the index, despite the recent market declines. We believe this is prudent, as specialized investment processes and strategies that can adapt to the local market’s unique and growing idiosyncrasies will continue to be the optimal path for investing in China.

1 “Anti-Hero”, by Taylor Swift

2 “A Place in This World”, by Taylor Swift

3 https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Caixin/Hong-Kong-Shanghai-Shenzhen-connect-lists-add-1-000-stocks

4 “My Own Way”, by Taylor Swift

5 “ME!”, by Taylor Swift

6 “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together”, by Taylor Swift

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.