Combatants are preparing for battle. The summer of 2024 threatens to ignite transnational conflict with an unprecedented array of flashpoints never seen in the modern world. For the first time in history, the Cricket World Cup, Copa America, Euro Cup, and the Olympic Games will take place in the same summer.

Already, this historic season of global sport is colored by global geopolitics on several fronts. Russia and Belarus were completely banned from the Euro Cup as well as all team sports at the Paris Olympics due to the war on Ukraine (individual Olympic athletes can apply to compete under a “non-affiliated” banner). Meanwhile there continues to be calls for Israel to be banned from the 2024 Paris games due to the ongoing war in Gaza. Tensions in France following the recent elections area already high in the Olympic host nation, where the Olympics themselves are already highly unpopular. Tensions within the games were already set to run high as French law forbids the wearing of hijabs and other headscarves during athletic events, setting the stage for protests by athletes, diplomatic schisms, and the intensification of cultural and religious conflict over the games.

But while geopolitics are roiling the world of sports (or sports are roiling global geopolitics), what are the market implications to this backdrop of transnational frictions? After all, since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the S&P climbed by over +27%, global equities have climbed +16% and although Russian oil was slapped with export restrictions, global oil prices have decreased by -14%. Similarly, since the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and the ongoing war in Gaza, Israeli stocks have gained +10%, Arab markets broadly are up +3%, and oil prices are flat. Indeed, apart from a few punctuated episodes here and there (the first Gulf War, 9/11, the Eurozone crisis, etc.) the last 40 years have seen geopolitics as largely a tailwind to global risk assets and not a source of concern.

We believe the time of geopolitical tailwinds are largely behind us, and investors need to move beyond expected return models built through analyses of risk premia and asset correlations and reacquaint themselves with the new international order and its implications for markets. Here we will address:

- How key geopolitical and political phase shifts underlying unfolding events will affect the macro environment, and ultimately, risk asset returns.

- How asset owners should evaluate geopolitical and political events.

Then we will highlight eight specific takeaways on assets and markets that will be materially impacted by these phase shifts. But first, to understand where we are and where we are going, let us briefly revisit how geopolitics have been an underappreciated tailwind for the past 40 years.

A Benign Invisible Hand

Investment lore attaches almost mythical status to the late former Fed Chair Paul Volcker who like John Wayne conquered the Wild West of runaway inflation. But we could not have enjoyed low and stable interest rates and inflation for the ensuing 30 years without the deflationary impact of China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization and concurrent access to relatively cheap labor in China, Eastern Europe and Latin America. Indeed, investors’ obsession with every FOMC pronouncement and the anchoring of long-term inflation expectations at 2% suggest that markets continue to under appreciate underlying factors that ultimately determined the durability of Volcker’s and all Fed policy.

Corporate earnings and financial assets were also buoyed by the laissez faire tenets of the so called “Washington Consensus” popularized by U.S. President Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, which favored regulation-light policies, central bank independence and globalization. Politicians on both the right and left hewed to these tenets. In fact, after he signed the bills on NAFTA, reformed welfare and amended the Glass Steagall Act that lifted restrictions on the banking industry, former fed chair Alan Greenspan hailed Clinton as “the best Republican president we’ve had in a while!”

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 provided a geopolitical peace dividend in that the world was no longer divided into two competing spheres. Thus capital, trade and production could go wherever it could be most efficiently deployed. The end of the Cold War also boosted productivity by commercializing access to advanced military research. Though the rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union led to spending on unproductive endeavors (such as the proxy war in Vietnam), it also spurred state investment into R&D, which when commercialized, massively boosted productivity. The internet for example began as a military communication system. And the world continues to coast on the ancillary benefits of putting a man on the moon or trying to deliver a nuclear payload across the planet.

Finally, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ushered in a unipolar order wherein the United States became the singular global superpower which could impose a so-called rules-based international order and a network of global alliances that coordinated policy to uphold it. Even though America sometimes thwarted its own rules, this rules-based order expanded globalization which in turn, reduced inflation and provided a framework for addressing successive global crises.

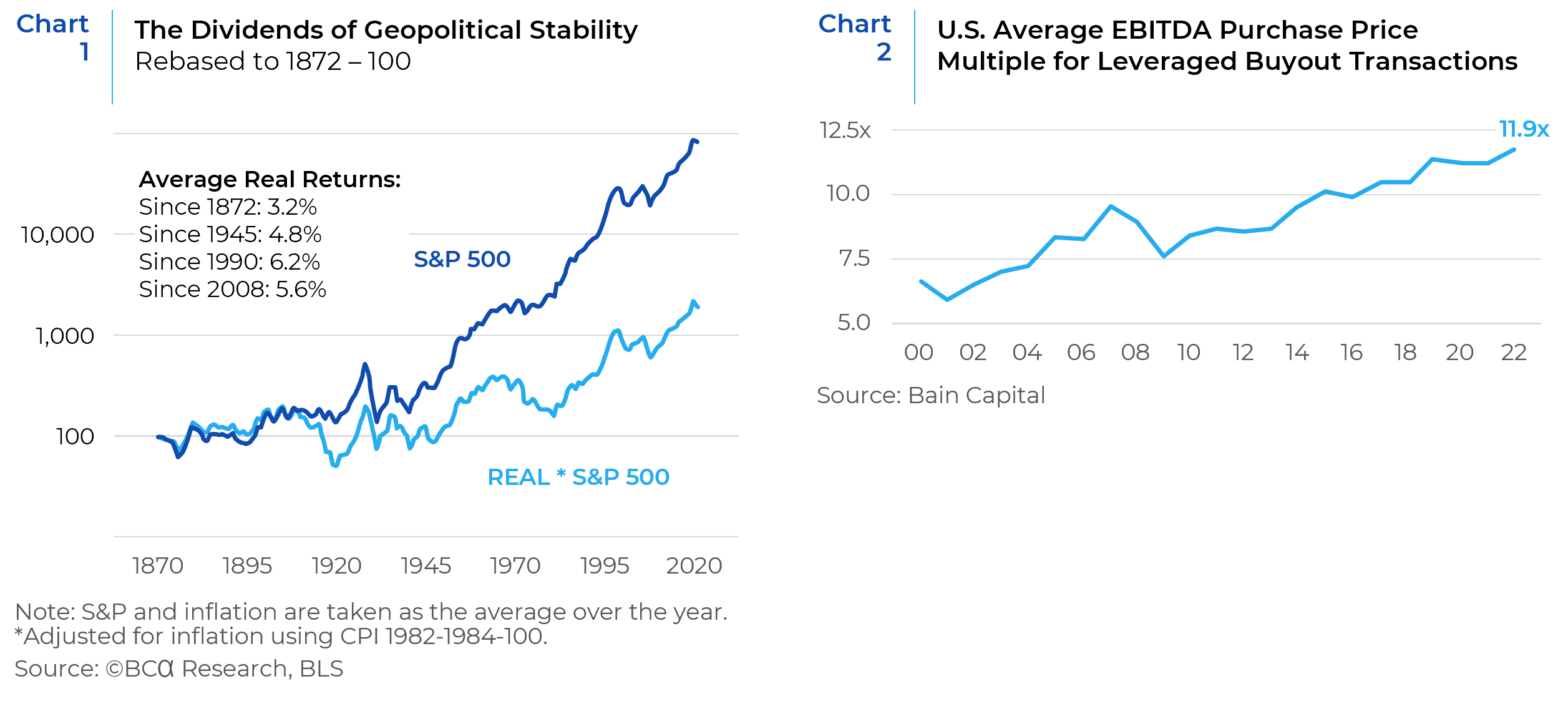

All these factors favored risk assets. Accordingly, the average annual real return on US equities since 1872 has been +3.2%. During the general peace and prosperity following World War II, stocks returned +4.8% per year. But in the post-Cold War period they returned +6.2% per year (see Chart 1).

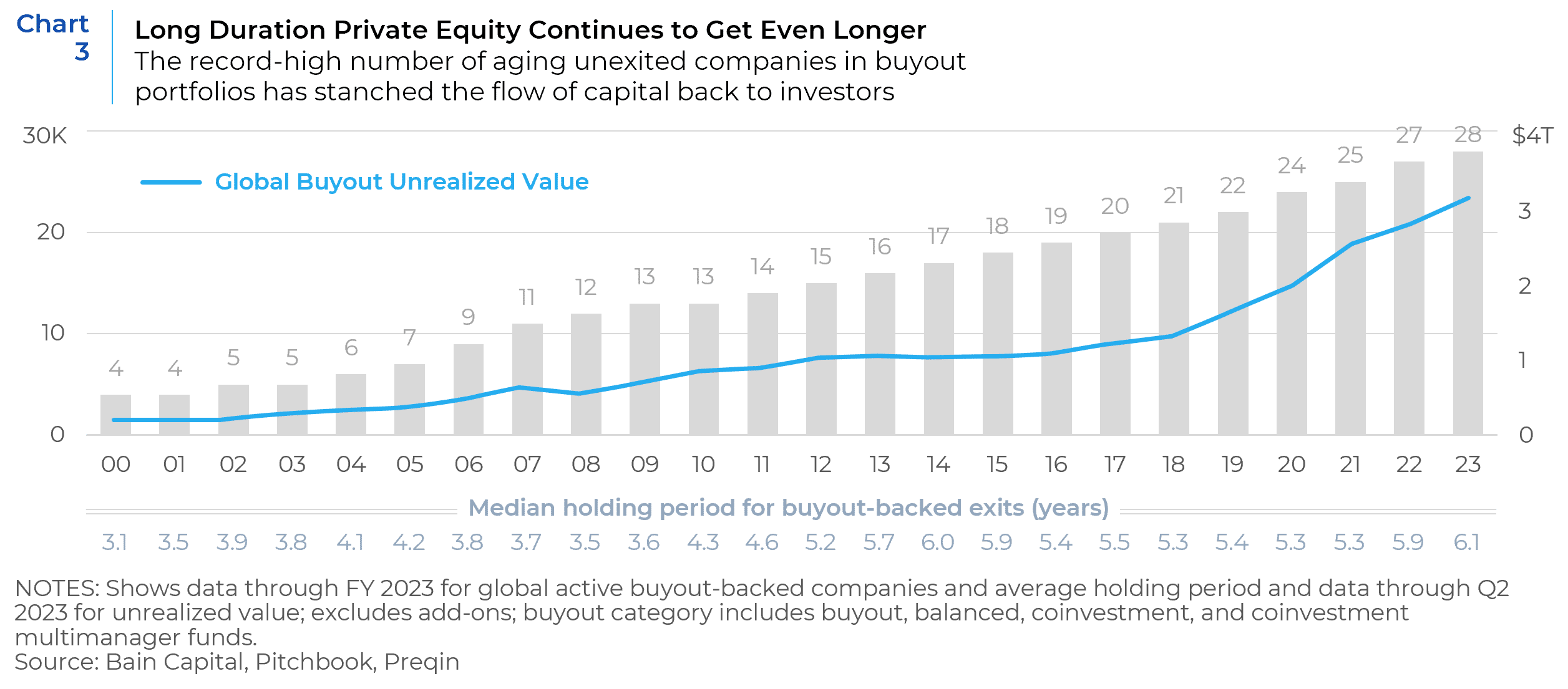

For asset owners, it paid to simply be long equity, duration, and credit. The low cost of capital also boosted the investment premium for less liquid assets while financial engineering further goosed returns. The most direct beneficiaries were passive cap weighted equity indexes, long duration credit and private equity. Indeed, according to a study by Bain, over 60% of the value created by top leverage buyout funds was due to financial engineering and terminal value expansion – both of which are flattered by low interest rates. Accordingly, private equity now faces headwinds from its own successes in driving up valuations (see Chart 2). Not surprisingly, week post-2021 exit multiples are forcing GPs to extend duration in what was already a long duration asset through vehicles such as continuation funds. In the absence of robust exit opportunities, GPs are also exploring net asset value or NAV financing collateralized by their fund’s portfolio holdings to help bolster the return of capital (or DPI) that LPs have come to expect and depend on. (see Chart 3).

Winds of Change

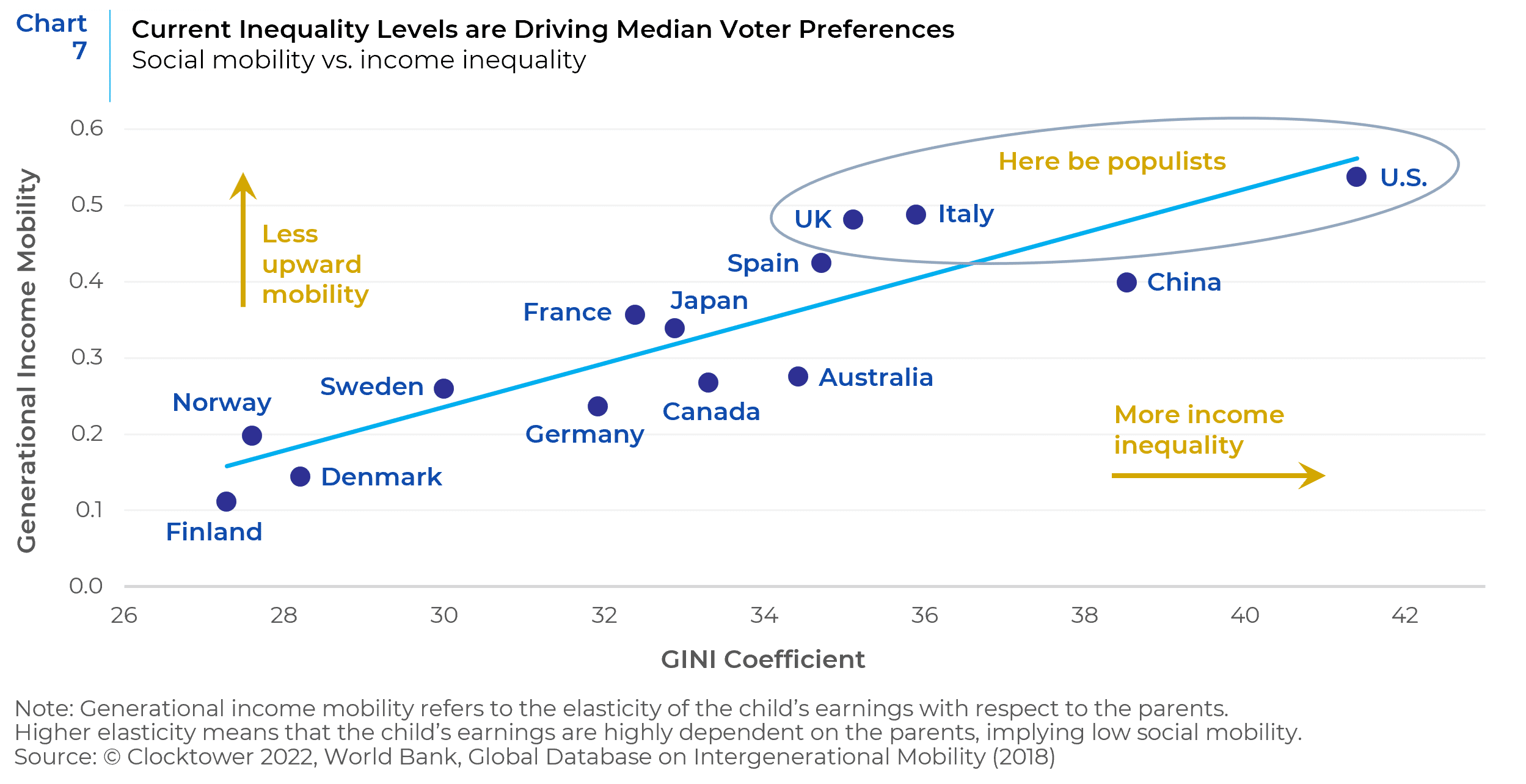

Long duration assets benefit disproportionately from low volatility and environments of predictability and lack of uncertainty. Unfortunately, the bedrock for a global order of low uncertainty is being challenged on two basic fronts. The first is a shift in median voter preferences which, due to entrenched income inequality and diminishing social mobility, has grown disenchanted with the Washington Consensus tenets of laissez faire capitalism, unfettered globalization, and fiscal and monetary orthodoxy. In response, political leaders on both the left and right are increasingly abandoning the Washington Consensus, eschewing fiscal austerity, and embracing trade protectionism that in turn have led to a resetting of global inflation and interest rate expectations.

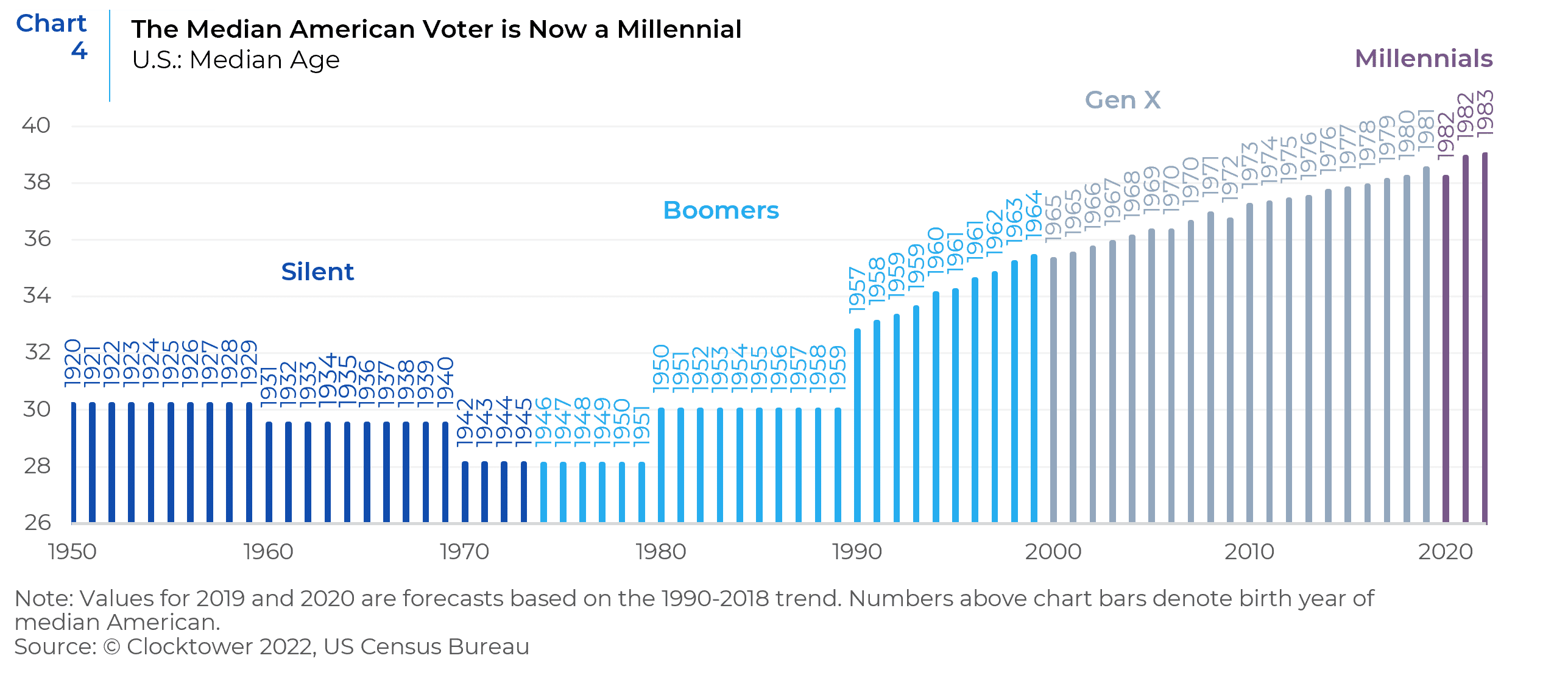

A big contributor to the pendulum shift in median voter preferences – at least in the US – is demographics. From 2020 onwards, the median voter in America is a debt-ridden Millennial facing stagnant wages and massively appreciated middle class goods, in housing, food and education (see Chart 4).

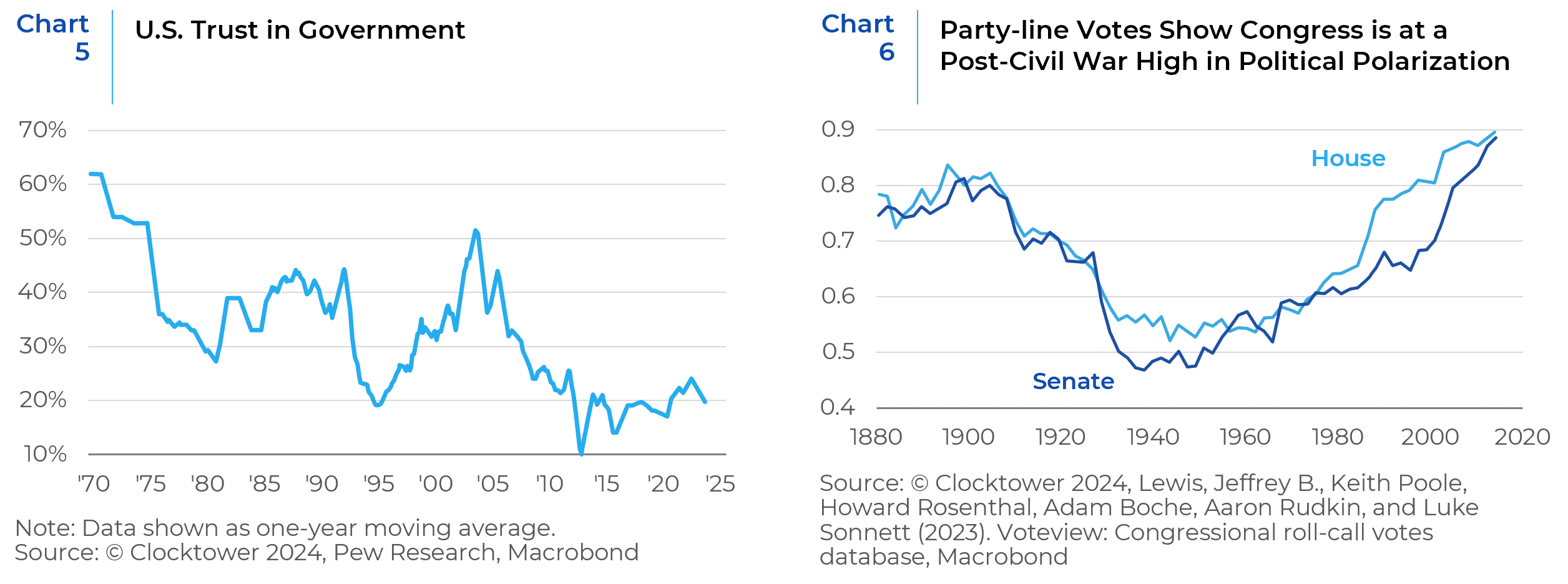

The marginal Millennial voter has come of age in a time of declining trust in government (see chart 5) that is at least coincident with (if not caused by) increased political polarization that has reduced the stability and efficacy of the legislative process in America (see chart 6).

This generation of Americans has little experience with policymaking by compromise, is accustomed to extreme political rhetoric and increasingly, a winner-take-all approach to elections to legislating. Moreover, the economic conditions that America finds itself in today, with rampant income inequality and limited economic mobility, is fertile ground for continued attraction to populist ideologies and politicians for the foreseeable future.

This resetting of the median voter’s preferences will drive market relevant policies for the rest of the decade (at least), regardless of which party occupies the White House or the Congress. Just like politicians on both the right and left hewed to the Washington Consensus, this pendulum shift in median voter preferences will lead them to hew to what geopolitical strategist Marko Papic calls the Buenos Aires Consensus, which shews austerity and policy orthodoxy in favor of fiscal profligacy, protectionism and in some cases, populism — all of which are inflationary.

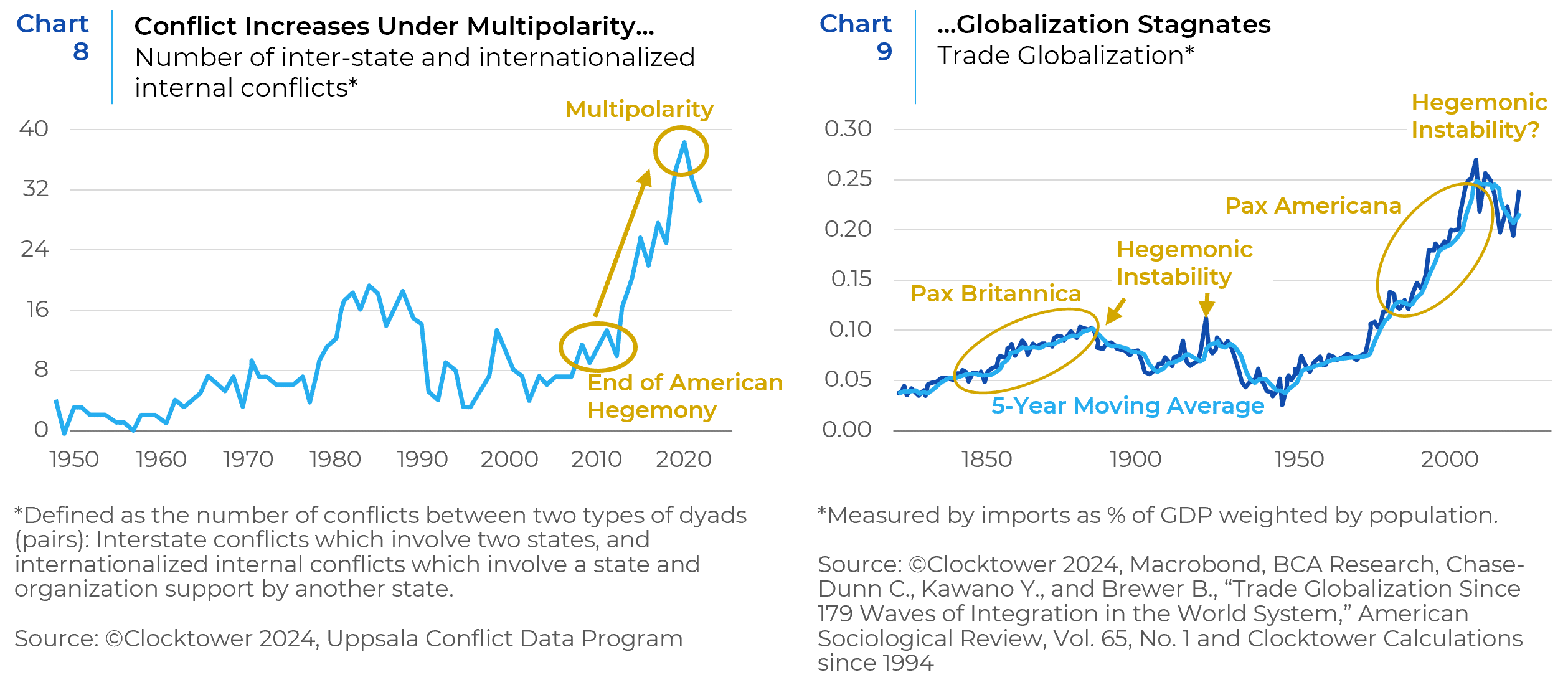

The second front is a shift away from a unipolar to a more volatile multipolar geopolitical order, manifested as waning American influence, increasing challenges to its rules-based international order, and a more fragmented global financial system.

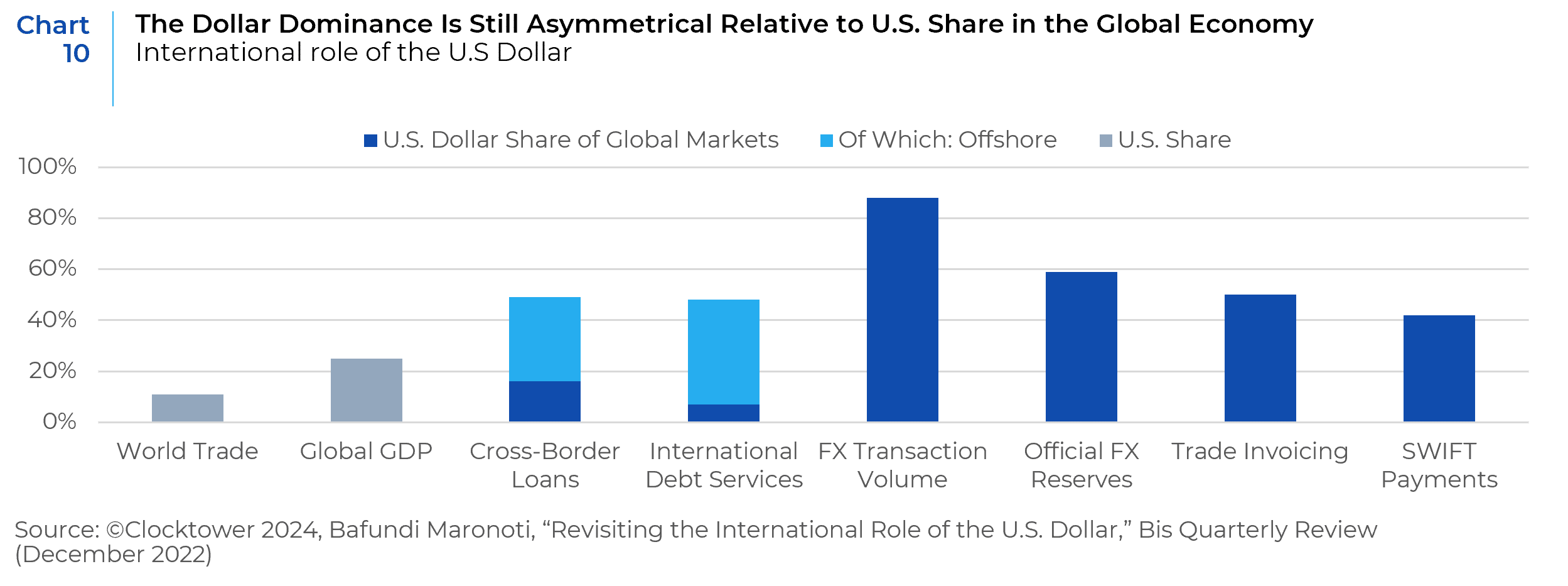

It is important to note that America’s absolute power has not diminished. It has the world’s most powerful military, the third-largest population, and unlike other world powers, its working-age population is still growing (albeit largely through immigration which is also fraught with its own political tensions). America also dominates global economic and financial markets and the US dollar’s reserve currency status remains strong.

But while America’s power remains undiminished in absolute terms, its relative influence to compel other nations to subsume their own national interests to comply with its geopolitical imperatives has waned. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush easily assembled support in the United Nations to back the U.S.’s for the 1st Gulf War in Kuwait. While President Biden has corralled NATO to support Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s invasion, this time around, China, India, Turkey, and Brazil, have all remained steadfastly neutral as they pursue their own national interests. This is due to what Fareed Zakaria calls the rise of the rest in that the so-called third world countries comprised 30% of the global economy in 1990. Today they account for 50%.

Indeed, Russia’s attempt to reassert its regional dominance over its former vassal states; China’s assertions in the South China Sea, and Japan’s consequent efforts to re-militarize; as well as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran’s competition for regional authority, are also symptomatic of a gradual shift to a more multi-polar geopolitical power structure. This in turn is also inflationary, as it adds uncertainty to supply chains and increases the needs for redundancy, larger inventories, and cost hedging.

The continued fragmentation of the global financial system is also symptomatic of the gradual diffusion of economic power. While the USD remains by far the single most dominant currency globally on any metric (see chart 10), it is already losing market share as a reserve holding of central banks and as a means of exchange for trade payments. The rise of electronic payments will make it easier to disintermediate old school FX markets, while the weaponization of the USD through American sanctions policy adds impetus to explore new alternatives.

So far recent military events have not been market relevant. But they could be if, for example, the strategic rivalry between China and the U.S. escalates into a meaningful military or trade confrontation. That’s why, in addition to the perennial saber-rattling over Taiwan, I am also eyeing the Sino-Filipino conflict which could become a modern Lusitania. The U.S. and Japan both have defense pacts with the Philippines, there’s a populist in the Philippines and a strongman with an ego in China.

Rethinking Your Thinking

To reincorporate the new geopolitical paradigm into their investment decision-making, asset owners need a new framework. I prefer the constraints vs. preferences framework which minimizes our and the media’s tendency to focus on personalities and instead focuses on the material constraints facing policymakers. Ideologies, values, and preferences break like waves on the rocky shore of their material constraints. No matter who wins the US presidency, they will respond to the material constraints of median voter preferences, global geopolitics, and hopefully, the constitution. It is why presidential campaign promises often go undelivered. As a case in point, Obama did not close Guantanamo Bay. Trump did not repeal Obamacare and the Biden Administration kept Trump’s trade policy, ratcheting up attacks against China while adopting the Make America Great Again (MAGA) ideological line against globalization.

Whoever prevails in the November 2024 U.S. presidential election, the next president will be constrained by the desires of the median voter and the complexities of a multipolar global environment. Just like the laissez faire tenets of the Washington Consensus pushed both liberal and conservative parties towards economic orthodoxy around trade and fiscal austerity; the Buenos Aires Consensus, will push leaders on both sides towards protectionism, cross border investment controls and fiscal profligacy. All these shifts are obviously highly market relevant as persistent drivers of inflation and uncertainty. Where Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris (the presumptive Democratic nominee) differ massively is on social issues, but also in terms of the policy constraints they are each likely to face if elected. If Trump wins, he would be highly likely to enjoy a unified Republican Congress. Due to the Senate’s two-year electoral cycle – during which roughly a third of all seats are up for reelection – the Democratic Party will have to defend seven of the nine competitive Senate seats in the 2024 election. Further, if Trump wins, it stands to reason that the Republican Senate candidates will win state-wide races in competitive states in Montana, Ohio, and Wisconsin. If Harris wins, she will have to cross the finish line in a tight race which is unlikely to carry Democrats the House, which is far less sensitive to national and state-wide races.

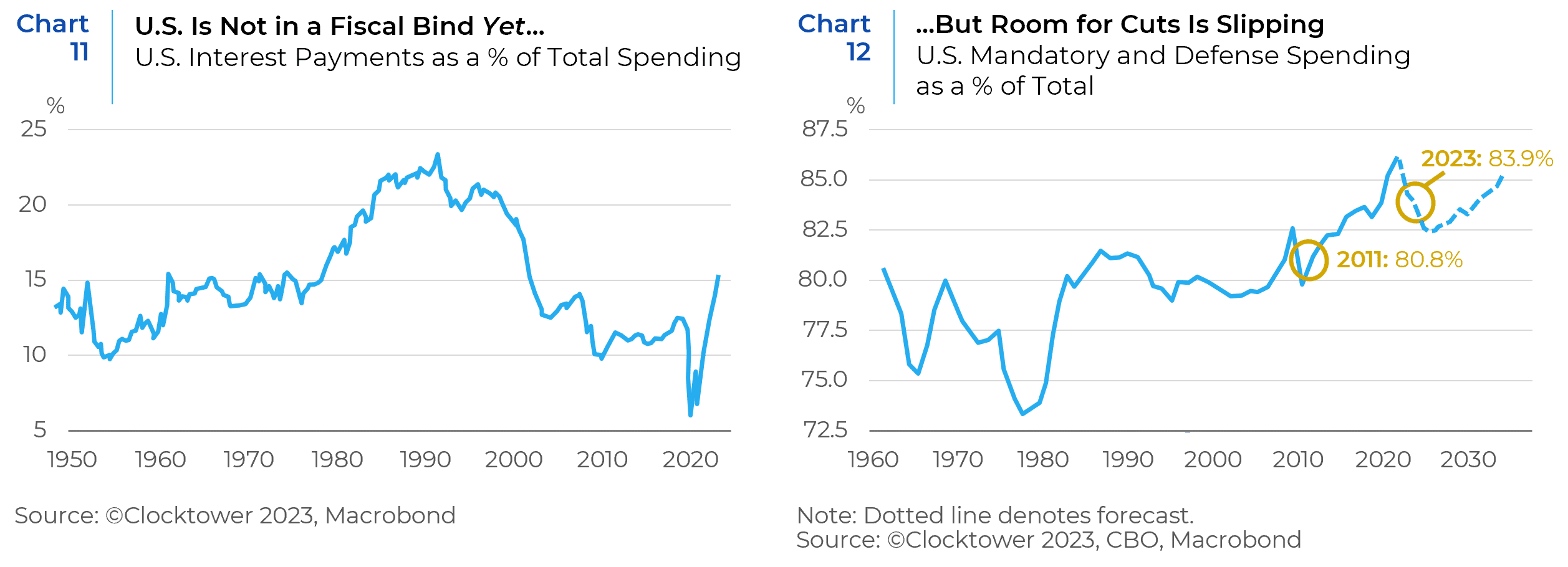

A second consecutive Democratic presidency would not only see their policies held in check not just by a divided congress, but also by America’s bureaucratic caste, as has been the case with every other president in modern US history. Donald Trump, however, has elucidated a strong preference for reforming America’s technocracy; or, to use his more colorful phrase, “drain the swamp.” It is in fact a key tenet of his policy platform. The most immediately market relevant change would be any attempt to politicize the Fed, especially with a compliant Congress. There is already precedent for the president firing the Fed Chair (President Truman forced Thomas McCabe to retire) before their term expires. That’s why a Trump presidency would simply accelerate the shift towards a Buenos Aires Consensus, pro-inflationary outcome.

Eight Big Investor Takeaways

- The era of unfettered freedom to invest anywhere is behind us, and we will likely face a minefield of restrictions on investments in certain sectors and regions. Cross-border investment-screening programs by the United States (e.g. CFIUS) and others will become more robust and extend to outbound investment, not just inbound investments. Accordingly, last August President Biden signed an executive order to vet investments in “sensitive technologies” (meaning advanced chips, quantum computing and artificial intelligence) in “countries of concern” (meaning China). The implication is that national security trumps investment returns.

- The global financial system will continue to fragment. While no single currency is likely to overtake the dollar as a single reserve currency or global means of exchange for the foreseeable future, in betting on the greenback or the field, investors would be well advised to at least hedge with the field. Moreover, continued political disfunction and fiscal profligacy could easily force a showdown with the bond market which would force the U.S. government to either undertake fiscal consolidation or financial repression measures. The latter would be bearish for the US dollar.

- In addition to the aerospace and defense sector that will benefit from geopolitical volatility, utility companies and their capex supply chains will become the new growth stocks because they are at the center of highly energy intensive AI models and data centers, electric vehicles as well as the reshoring of industrial production in the U.S. and Europe.

- While the Washington Consensus stabilized and subdued inflation, the Buenos Aires Consensus will do the opposite. Inflation will stay sticky for a while, anchoring the yield on Treasury bonds the 3% -6% range for the decade. The set it and forget it long duration play of the post-GFC period is over. Credit selection will be even more important, especially since as the operating environment for companies becomes more difficult.

- Among private market strategies, infrastructure and private credit’s diversification benefits will gain ground; but GPs ability to invest in a more difficult operating environment and successfully execute workouts will obviously become more important. Additionally, growth equity’s focus on cash-generating, positive-income portfolio companies in need of expansionary investment will gain ground over buyouts, the staple of most asset owner’s PE portfolios, though the capacity of the former is more limited, leading to a needed re-sizing of private equity markets. This environment will also buoy secondaries and NAV lenders because of their ability to provide liquidity to LPs and capital flexibility to GPs, while allowing them to extend the operating runway for aging fund assets. The supply-demand dynamics there are especially appealing because according to Pitchbook, one third of the $10 trillion in NAV held in private funds is at least seven years old, while there is only $200 billion in secondaries dry powder. Asset owners should emphasize how GPs create value through operating leverage and manage DPI vs. those who track record was primarily boosted through higher exit multiples.

- North American Reindustrialization – Nearshoring/Re-shoring and green energy will create a new cap ex cycle. This is bullish for commodities, industrials, and metals. It’s also bullish for wages but not so bullish for corporates, profitability, and equity markets.

- A multipolar world which creates competition between the Great Powers accrues its benefits disproportionately to mid-tier, geopolitically promiscuous states. India and Latin American countries such as Mexico, Brazil and Chile are big enough to flirt with each Great Power and shop around for the best deal without incurring the wrath of either. In Latam, trade with China has long overtaken trade with the U.S. thus primary fiscal balances for Brazil, Mexico and Chile have already turned positive. Inflation is now below pre-pandemic levels in all but Colombia. These markets would also be expected to benefit from the previously mentioned capex and commodity super cycle. India, despite buying lots of cheap Russian oil – which is helping them finance infrastructure and diversify their supply chains – continues to be the darling of Washington and the financial and tech sectors. The Modi reforms are also making India more productive, and India is benefiting from the creation of a true national economy in the same way that the U.S. benefited from its development in the late 1800s. India will continue to be the growth story of this decade that China was in the 2000s.

- The Japanese comeback is durable. First, Japan is another geopolitically acceptable alternative to China. Second, Japan’s equity market sector mix is conducive to a capex cycle because of its industrials and materials companies and the fact that it doubles the US share of labor in manufacturing. And as we recently wrote about, Japanese labor has quietly emerged as the lowest cost labor market among developed markets. Very small green shoots of growth, and the end of deflation, are all that is needed to unlock trillions of dollars in Japanese household cash into the global economy, and that data indicates this long awaited “re-risking” of Japanese portfolios is finally taking root. The net effect will be a 2-3 trillion dollar “stimulus”, that looks likely to flow about half to Japanese equities and half to the rest of global equities (currently mostly U.S.), over the next 10-15 years.

In sum, the changes in global geopolitics are scrambling historical investment assumptions around inflation, interest rates, liquidity management, supply chains, and the freedom to invest wherever provides the highest ROI. Global sport is already incorporating geopolitics into their frameworks of operations. It’s time asset owners also get in the game.

1 https://www.bain.com/globalassets/noindex/2024/bain_report_global-private-equity-report-2024.pdf

This report is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation to invest in any product offered by Xponance® and should not be considered as investment advice. This report was prepared for clients and prospective clients of Xponance® and is intended to be used solely by such clients and prospective clients for educational and illustrative purposes. The information contained herein is proprietary to Xponance® and may not be duplicated or used for any purpose other than the educational purpose for which it has been provided. Any unauthorized use, duplication or disclosure of this report is strictly prohibited.

This report is based on information believed to be correct but is subject to revision. Although the information provided herein has been obtained from sources which Xponance® believes to be reliable, Xponance® does not guarantee its accuracy, and such information may be incomplete or condensed. Additional information is available from Xponance® upon request. All performance and other projections are historical and do not guarantee future performance. No assurance can be given that any particular investment objective or strategy will be achieved at a given time and actual investment results may vary over any given time.